I: The Lurker Below

Part II: The Urge to Eliminate

Is the urge to eliminate, to purge from within the people we deem our internal enemies, simply a natural impulse buried deep in our psyches -- irresistible, ineluctable, inevitable? Certainly, CNN's Glenn Beck seems to think so.

This summer, Beck was arguing over the airwaves that if there were further terrorist attacks by Muslims on American soil, that concentration camps were all but a fait accompli, and that "Muslims will see the West through razor wire if things don't change":

- All you Muslims who have sat on your frickin' hands the whole time and have not been marching in the streets and have not been saying, 'Hey, you know what? There are good Muslims and bad Muslims. We need to be the first ones in the recruitment office lining up to shoot the bad Muslims in the head.' I'm telling you, with God as my witness... human beings are not strong enough, unfortunately, to restrain themselves from putting up razor wire and putting you on one side of it. When things -- when people become hungry, when people see that their way of life is on the edge of being over, they will put razor wire up and just based on the way you look or just based on your religion, they will round you up. Is that wrong? Oh my gosh, it is Nazi, World War II wrong, but society has proved it time and time again: It will happen.

Beck is at least right about one aspect of this: the compulsion to purge society of a designated threat is deeply buried in our psyches, both individually and collectively. Its origins, in many regards, date to earliest humanity. Indeed, it can properly be said to arise from the same primitive impulse -- the desire to dominate others, by violence if necessary -- that underlies humankind's most destructive enterprises throughout history: war, slavery, torture, genocide.

Eliminationism is, however, no more inevitable than any of these other impulses, against which mankind has over the centuries, in fits and starts, struggled to overcome. Slavery is considered a dead letter in modern global society, though aspects of it can still be found in some of the world's darker corners. Genocide and torture have been outlawed by the international community and are considered the most grievous of war crimes. And although American presidents are still capable of blithely making war, it is still widely understood to be among mankind's greatest scourges, a blot that only the most amoral among us undertake as anything but a last grim resort.

In its final outcome, eliminationism is almost indistinguishable from genocide, except for one aspect: it is genocide directed against an enemy within instead of without. But in all other aspects, particularly the utter objectification of the Enemy to the point of demonization, they are closely related.

And genocides, of course, have been with us throughout much of human history. The Bible records a number of them, including the killing and enslavement of the Israelites by the Egyptians; the extermination of the Canaanites by the Israelites, commanded by God (Deuteronomy 20:16-17), as well as the incomplete genocide commanded by God of the Amalekites at the hands of King Saul (Deuteronomy 25:19); and the massacres of various Middle Eastern peoples carried out by the Assyrian and Babylonian empires. Other genocides buried in the mists of history include the Scythian slaughter of Cimmerians recorded by Herodotus, who described these massacres occurring in the vicinty of the Black Sea as the Scythians swept westward of the Black Sea in the 7th century B.C.

Genocide became an institutional feature of Empire under the Romans. Julius Caesar slaughtered more than half of the Helvetii in conquering present-day Switzerland); he also massacred over a million Gauls and destroyed 800 cities in present-day France. The Romans also completely destroyed the city of Carthage in the Third Punic War, as well as the city of Jerusalem in A.D. 70; the populations of both cities were either killed or enslaved, and both cities were later rebuilt and repopulated by the Romans.

Genocide is a constant in much of the rest of the history of the world's violence as well. Genghis Khan and his sons, in the pursuit of their massive Mongol empire, systematically massacred millions of civilians throughout Eurasia during the 13th century. This includes the sacking of Baghdad in 1258, in which some two-thirds of the city's 1.5 million inhabitants were slaughtered. Likewise, the Islamic conquest of South Asia saw the massacre of thousands of Hindus, Buddhists and Jains, mostly in periodic outbreaks that in many cases represented an effort to suppress dissident factions.

The vast majority of these genocides were directed at ostensibly external enemies -- either the occupants of neighboring territories whose activities were deemed threats to the perpetrators, or people whose lands were coveted for purposes of territorial expansion. All of them took place in the context of war and conquest.

Yet throughout history, war and conquest have not only shaped our societies but have been products of them. Warmaking has always been inextricably bound up with cultural conceptions of heroism and virtue, and these conceptions have in turn driven the shape of how we wage war -- including the urge eliminate.

The adulation of heroes arises out of a basic human need, as the late Ernest Becker put it, to feel good about ourselves, to know ourselves as heroes. In the West, the heroic task historically has entailed energetically taking up arms to redeem the world. It also entails creating an enemy and naming him; the heroic warrior, after all, needs an enemy against which to fight, something to give his life meaning. The drama that results is a holy war to drive out an alien darkness or disease, and it is a drama that has played out innumerable times throughout the long history of the West.

Yet, as James Aho observes in This Thing of Darkness: A Sociology of the Enemy, the heroic dynamic has played out differently in different cultures. In the East, he notes, the martial-arts hero is perfected by becoming "absorbed in a cycle that is larger than himself," subsumed by eternal spiritual principles with which he has become aligned. But this is not the case in the Occident:

- In civilizations that have come under Judeo-Christian and Muslim influence -- which is to say, among others, modern Europe and America -- chaos is experienced as the product of disobedience regarding ethical duties, not mere ritual infractions, as these have been revealed through prophecy. Here, then, the heroic task becomes one not of passively yielding to the Way but of energetically taking up weapons to reform the world after the personal commandments of the Holy One. The Occidental holy war functions to stereilize the world of an alien darkness or disease, not to reconcile man to its inevitability, particularly its inevitability in himself.

... For adherents of sacred and secular Occidental faiths (such as Marxism, liberalism, or fascism) the world is "fallen" or "problematic," hence susceptible to reform. But no reform movement can make the world over all at once in its entirety. Therefore, each focuses its indignation and redemptive energy on a "fetish" of evil -- a despicable act, a heretical belief, a foreign place, an alien people, a criminal person -- that is to be fettered, expulsed, or exterminated.

This expiative impulse, in the West at least, became closely associated with Christianity during the early Middle Ages, especially in the later phases of the Holy Roman empire, when Church doctrine regarding the nature of sin developed into a deep psychological fixation regarding the impurity of the flesh.

Historian David E. Stannard's text American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World explores these historical roots of genocide in European culture in some depth. As he observes (pp.154-155), the Augustinian doctrine of worldly sin equated all the natural world with evil and brutality, including such natural impulses as sex:

- The idea is hardly a Christian invention, then, that immoderate enjoyment of the pleasures of the flesh belongs to the world of the brute, and that abstinence, modesty, strictness and sobriety are to be treasured above all else. Still, it is understandable why subsequent European thought would regard Greece and Rome as realms of carnal indulgence, since subsequent European thought was dominnated by Christian ideology. And as the world of the Christian fathers became the world of the Church Triumphant, while fluid and contested mythologies hardened into dogmatic theology, certain fundamental characteristics of Christianity, often derived from the teachings of Paul, came to express themselves in fanatical form. Not the least of these was the coming to dominance of an Augustinian notion of sex as sin (and sin as sexual) along with a larger sense, as Elaine Pagels puts it, that all of humanity was hopelessly "sick, suffering, and helpless." As late antiquity in Europe began falling under the moral control of Christians there occurred what historian Jacques le Goff has called la deroute du corporal -- "the rout of the body." Not only was human flesh thenceforward to be regarded as corrupt, but so was the very nature of humankind and, indeed, so was nature itself; so corrupt, in fact, that only a rigid authoritarianism could be trusted to govern men and women who, since the fall of Adam and Eve, had been permanently poisoned with an inability to govern themselves in a fashion acceptable to God.

... The Christian leader ... stood apart from all others by making a public statement that in fact focused enormous attention on sexuality. Indeed, "sexuality became a highly charged symbolic marker" exactly because its dramatic removal as a central activity of life allowed the self-proclaimed saintly individual to present himself as "the ideal of the single-hearted person" -- the person whose heart belonged only to God.

Of course, such fanatically aggressive opposition to sex can only occur among people who are fanatically obsessed with sex, and nowhere was this more ostentatiously evident than in the lives of the early Christian hermits ...

Stannard later offers, by way of illustration, the following explanation from the poet and Franciscan monk Giacomo di Verona, describing the origins of human nature:

- In a very dirty and vile workroom

You were made out of slime

So foul and so wretched

That my lips cannot bring themselves to tell you about it.

But if you have a bit of sense, you will know

That the fragile body in which you lived,

Where you were tormented eight months and more,

Was made of rotting and corrupt excrement ....

You came through a foul passage

And you fell into the world, poor and naked ...

... Other creatures have some use:

Meat and bone, wool and leather;

But you, stinking man, you are worse than dung:

From you, man, comes only pus ...

From you comes no virtue,

You are a sly and evil traitor;

Look in front of you and look behind,

For your life is like your shadow

Which quickly comes and quickly goes ...

As Stannard explains, such "learned and saintly medieval urgings" were part of a medieval worldview that created a culture that "became something truly to behold," one in which the effort to purge oneself of base sinfulness gave birth to a panoply of bizarre and painful self-inflictions. He cites a passage from a "not untypical" devout friar, described by Norman Cohn, who

- shut himself up in his cell and stripped himself naked ... and took up his scourge with the sharp spikes, and beat himself on the body and on the arms and legs, till blood poured off him as from a man who has been cupped. One of the spikes on the scourge was bent crooked, like a hook, and whatever flesh it caught it tore off. He beat himself so hard that the scourge broke into three bits and the points flew against the wall. ...

Eventually, this hatred of sex was expressed in an abiding misogyny that identified women with the putrefication of the natural world and the source of worldly evil. It also identified the outside world with untamed nature and thus with wanton sinfulness. As Stannard writes, "there also lurked in distant realms demi-brutes who lived carnal and savage lives in wilderness controlled by Satan."

This view of the "uncivilized" world as populated by creatures who were perhaps only passably human also preceded Christianity by several centuries. Greek poets like Homer and Hesiod often described an outside world populated by demigods and other half-human races. Pliny the Elder, in the first century A.D., described in his Natural History peoples of far-off lands with fantastic traits, including people whose faces are embedded in their chests, or have the heads of dogs, or hooves instead of feet, or ears so long or lips so large they use them as coverings. As this myth-making was incorporated into Christian culture, it was assumed that the strangeness of these "monstrous" races, linked to the outcast lineage of Cain, was product of their innate sinfulness and downcast nature. "So great was their alienation from the world of God's -- or the gods' -- most favored people, in fact," writes Stannard, "that well into late antiquity they commonly were denied the label of 'men.'"

Eventually, by the later Middle Ages, this fascination with "monstrous" races evolved into an interest in the "wild man" who it was believed inhabited the unexplored wildernesses of the world. Stannard writes:

- Hidden or not, however, the loins of the wild man and his female were of abiding interest to Christian Europeans. For, in direct opposition to ascetic Christian ideals, wild people were seen as voraciously sexual creatures, some of them, in Hayden White's phrase, "little more than ambulatory genitalia." Adds historian Jeffrey Russell: "The wild man, both brutal and erotic, was a perfect projection of the repressed libidinous impulses of medieval man. His counterpart, the wild woman, who was a murderess, child-eater, bloodsucker and occasionally a sex nymph, was prototype of the witch."

... In sum, the wild man and his female companion, at their unconstrained and sensual worst, symbolized everything the Christian's ascetic contemptus mundi tradition was determined to eradicate -- even as that tradition acknowledged that the wild man's very same carnal and uncivilized sinfulness gnawed at the soul of the holiest saint, and (more painful still) that it was ultimately ineradicable, no matter how fervent the effort. ...

However, these threats, like the heathen enemies of Muslim lands, were purely external. But the European populace was never entirely homogenous, and many of the non-Christians who lived in their midst were readily seen in the same heretical light as the Muslims who had been designated the Enemy; these Others' failure to conform was also taken as a certain sign of their sinfulness. The leading component of these non-Christians were Europe's Jews, who eventually bore the brunt of the Christian impulse to eliminate such sin with the scourge.

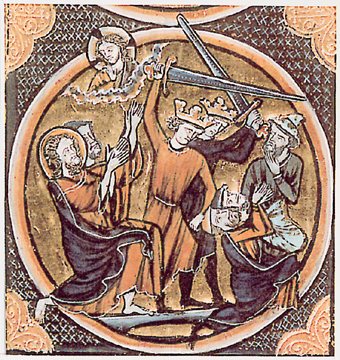

The first significant instance of this occurred in 1096 in the German town of Speyer, where 11 Jews who refused to convert to Christianity were killed; a few weeks later, in the city of Worms, some 800 Jews who refused to convert were stripped naked and summarily murdered. The killing spread to Mainz, Trier, Metz, and Cologne, Regensburg, and Prague. By the time the month was out, some 8,000 Jews had been massacred.

Their killers were primarily would-be Crusaders supposedly en route to the Holy Land, though many of them were simply bands of thugs who had decided to search out and destroy heretics who were not so far from home. Robert Chazan's In the Year 1096: The First Crusade and the Jews details how the First Crusade permanently changed the relationship of Jews to Christians in Europe, particularly in the way it made them wholly distinct within the European community, which they were no longer part of but were now considered to be "outsiders," as other "heretics" had already been designated.

The result was a nearly ceaseless litany of expulsions and pogroms. The most vicious of these were associated with the spread of the plague, or "Black Death," in the 14th century, for which the Jews were scapegoated. Rumors that they had spread the plague by poisoning wells led to the massacres of thousands of Jews in Germany, France, and Iberia; in Strasbourg, a town where the disease had not even hit, some 900 Jews were burned alive in 1349.

Meanwhile, some nations expelled Jews altogether. The practice began in France during the 12th-14th centuries, mostly as a way of enriching the French crown, which confiscated Jewish property even as it expelled Jews, first from Paris in 1182, then from the entirety of France in 1254, an act that was repeated in 1306, 1322, and 1394. In England, meanwhile, Edward I first accused Jews of disloyalty, then began constricting their "privileges" and forcing them to wear yellow patches; eventually, some 300 Jewish heads of household were taken to the Tower of London and executed. Eventually, all Jews were banished from England in 1290, which led to the deaths of thousands as they fled. No Jews were to be found in England for the next three centuries.

The urge to eliminate Jews reached a fever pitch, however, with the Inquisition, particularly the Spanish Inquisition:

- Nevertheless, in some parts of Spain towards the end of the fourteenth century, there was a wave of anti-Semitism, encouraged by the preaching of Ferrant Martinez, archdeacon of Ecija. The pogroms of June 1391 were especially bloody: in Seville, hundreds of Jews were killed, and the synagogue was completely destroyed. The number of victims was equally high in other cities, such as Cordoba, Valencia and Barcelona.

One of the consequences of these disturbances was the massive conversion of Jews. Before this date, conversions were rare, more motivated by social than religious reasons. But from the 15th century, a new social group appeared: conversos, also called new Christians, who were distrusted by Jews and Christians alike. By converting, Jews could not only escape eventual persecution, but also obtain entry into many offices and posts that were being prohibited to Jews through new, more severe regulations. Many conversos attained important positions in fifteenth century Spain.

The eliminationist impulse, as it always did, rose and fell with the cultural tides over the ensuing centuries in Europe. It particularly returned with a vengeance in the 20th century. The Armenian genocide of 1915-23 saw the massacre of hundreds of thousands of Armenians, and the expulsion of some 2 million of them, at the hands of the Ottoman government in Turkey. The genocide induced the Allied Powers of Britain, France and Russia to jointly issue a statement accusing the Turks of "a crime against humanity," the first time such a charge had ever been made.

But the eliminationist enterprise in Europe reached its apex only a few years later, when the German government embarked on the Holocaust, a project of extermination aimed primarily at Jews but including a broad range of people deemed unfit because of the contamination threat they were believed to pose to the purity of the Aryan race fetishized by the Nazis.

By that point, of course, Europeans had already been in America for some four and a half centuries. And not only had they exported the eliminationist impulse to the New World, but in doing so had given it fresh life, and a nearly limitless horizon.

Next: Bringers of Light and Death