Jack Benny and American Radio Comedy (Part 4)

/One of my Black students recently told the class that he assumed any media product to come up before the 1960s (and in some cases, well after) was problematic in terms of the racial dynamics between white and Black characters. What might surprise him about the relationship between Jack Benny and Rochester?

Let me first say that I, as a white cis woman in 2021 can’t presume to speak for anyone else, present or past, for how they might interpret such things as interracial relationships on an old radio comedy program, then or now, given that the commercial network radio system 1930s-50s was so completely dominated by white corporate power.

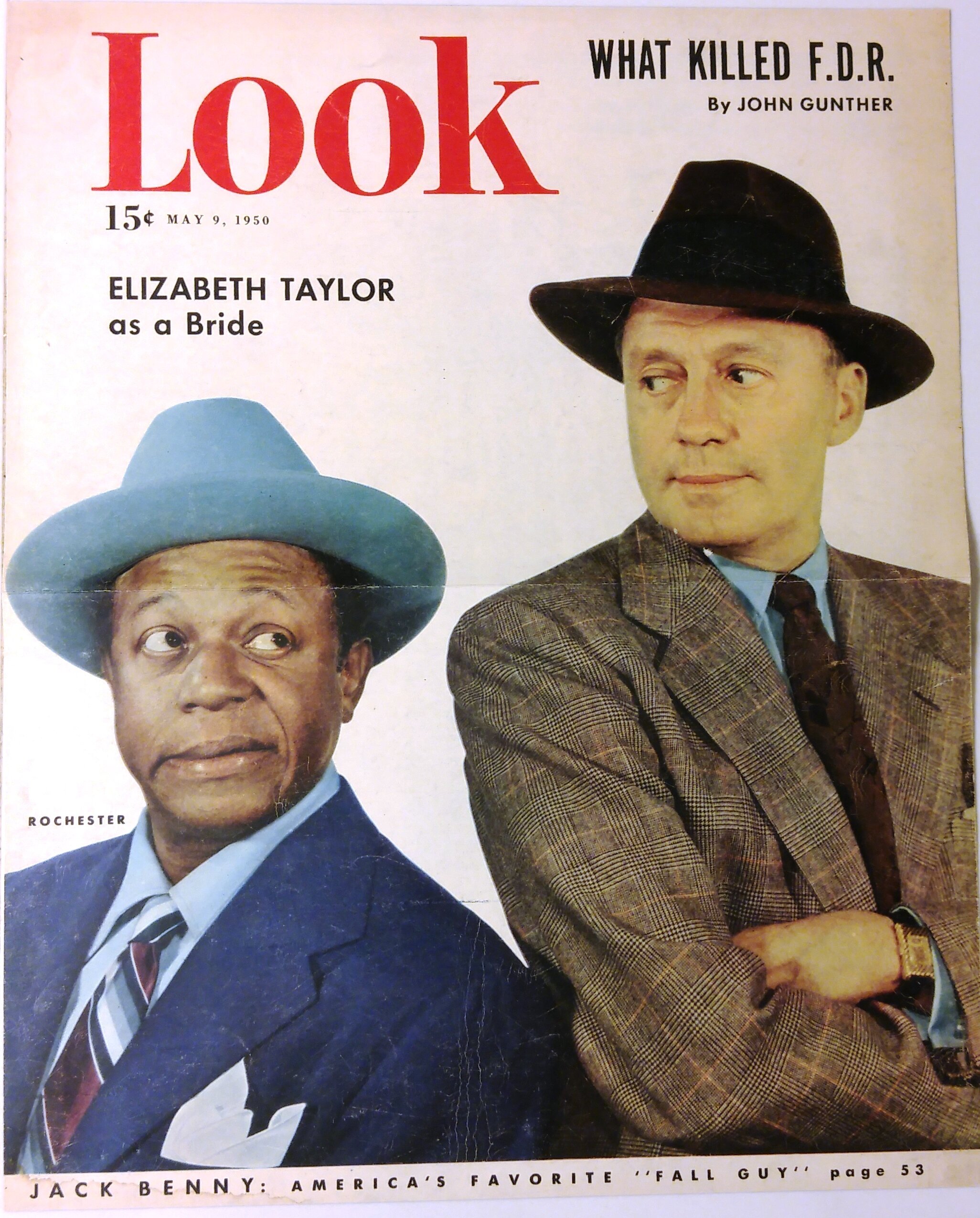

Back in the day, there was a range of interpretive positions that listeners of color might take (that could provide some interesting context for listeners today). Many African-Americans in the 1930s refused to listen to network radio, as almost no programs included black artists. (White actors routine spoke in ‘verbal blackface’ to voice small roles). When Eddie Anderson won the new, continuing role on the Jack Benny Jell-O comedy program in 1938 (one of the highest rated/most listened to shows on the air,) there was great interest in him and the show from the black community. The Chicago Defender and other African-American newspapers started carrying radio schedule listings, and they called the show the Rochester program with Jack Benny.

Rochester was wildly popular with both white and black listeners, for different reasons. African American listeners could enjoy the character’s sharp wit and puncturing of his boss’s ego (Rochester called his employer “Boss” more often than “Mr. Benny”, which was a small victory towards parity in the workplace). White listeners could feel that Rochester was “safe” as a servant eternally tied to housework. In my book I describe how Benny’s writers saddled the Rochester character in the first several years with belittling stereotypes (gambling, drinking, calling attention to his skin color, etc.).

But by World War II, Anderson’s character solidified a major continuing role and gained more autonomy to criticize the “boss.” Scripts allowed him to further develop his personality. Anderson simultaneously starred in several of the big-budget black cast musicals released from the Hollywood studios (such as Cabin in the Sky) as well as virtually co-starred in three very profitable Paramount films with Jack Benny.

After World War II, the younger generation of African-Americans grew increasingly impatient with the lack of progression in black representation on network radio and television. They expressed great frustration with roles limited to valets and maids and waiters, and that spilled over to anger at the older black performers who enacted these roles. Eddie Anderson got caught in the middle of this cultural change. His Rochester character in the latter radio years and throughout Jack Benny’s 15 years in television shared a remarkably intimate and convivial relationship with “the boss,” and their repartee is truly hilarious. Some have described their relationship as like the “Odd Couple” of later TV fame, two older men sharing the house and Rochester being like a domestic partner as well as Jack’s sharpest critic. Eddie Anderson, because he did few other performances apart from the Benny programs on his own in the 1950s and 1960s (ill health curtailed his career), has not been recognized sufficiently as a superb comic performer who brought a unique voice and sense of timing to amplify his continuing role in Benny’s narrative world.

I’d like to mention several other authors who have done marvelous work exploring the historical constraints and cultural contexts in which African-American performers at mid-century worked –

Petty, Miriam J. Stealing the show: African American performers and audiences in 1930s Hollywood.

Savage, Barbara Dianne. Broadcasting freedom: Radio, war, and the politics of race, 1938-1948.

Watts, Jill. Hattie McDaniel: Black Ambition, White Hollywood.

I especially point readers and scholars interested in the African-American actors’ experience in radio to this fabulous unpublished study ---- Edmerson, Estelle. "A descriptive study of the American Negro in United States professional radio, 1922-1953." MA thesis, University of California, Los Angeles, 1954. Edmerson undertook extensive interviews with black performers, and this report is a treasure. It is difficult to access, however, being available only on microfilm through interlibrary loan, but I have made a digital version that I can share with those who contact me.

Benny, like many of the comedians of that period, was Jewish, yet this is played down on the program. Can you speak about the ways that ethnic humor operated on the program? Was Mel Blanc (or Mr. Kitzel) there to deflect attention away from Benny’s own ethnicity. I just heard an episode where the Benny cast imitated the folks on Allen’s Alley to great effect and it really called attention to the more subtle ways that ethnicity was dealt with on the Benny show.

I am indebted to Holly A Pearse’s essay “As Goyish as Lime Jell-O?: Jack Benny and the American Construction of Jewishness,” which has helped me better understand Benny’s approach to ethnic representation in his own performance. Unlike many Jewish comedians who were raised in the densely-populated immigrant ethnic enclaves of New York City and the East Coast, Benjamin Kubelsky grew up in Waukegan, Illinois, the son of a Lithuanian Jewish barkeep and haberdasher in a relatively small industrial town an hour north of Chicago which had multiple ethnic groupings but only a small Jewish population. Renaming himself Jack Benny, as a performer, sought to emphasize a Midwestern white identity. He almost never incorporated Yiddish words or phrases into his vaudeville or radio performances.

There were long traditions of ethnic performance in vaudeville, of course, in which performers either exaggerated their own identities or took on ethnic costumes and language as part of their act. Historians have described how what Robert Snyder called these “voices of the city” brought constructed stereotypes (always a mix of benign and harmful) of Irish, Scotch, German, Italian, Greek, Scandinavian, Russian and other white immigrant ethnicities (as well as Black, Latino and Asian) to audiences in cities and towns across America. Humor involving these ethnic characters both reinforced stereotypes for audiences as well as sometimes made them seem part of a rich, vibrant American “melting pot.”

Radio inherited these approaches to representation of ethnicity from vaudeville. It seems that radio broadcast creation, with cost limitations on production on the one hand, and freedom to imagine characters (from the audience point of view) on the other, used ethnic voices quite frequently. In a storytelling world constrained by lack of visual cues, voice accent, tone and inflection carried a great deal of weight. Without other ways of distinguishing between different characters at the microphone, ethnic accents added an all-too-easy differentiation. I believe that in the case of Jack Benny’s early radio broadcast years, his writer Harry Conn often turned to ethnic voices among the supporting cast members to yield a quick laugh at the difference they represented from Jack’s midwestern voice. Conn used German, Yiddish, Greek or Scottish voices for bit players in Jack Benny’s skits. After Conn left the program in 1936, these ethnic voices were not used very often by the new writers (Morrow and Beloin) who chose to use the regular cast members more intensively.

It seems that Jack Benny and his writers offloaded Jewish identity onto a pair of part-time cast members over the course of his radio career. In the 1933-1936 era Jack Benny used comedian Sam Hearn to voice the character of Shlepperman. Shlepperman was a Jewish immigrant with city smarts and a heavy Yiddish accent. In the skits in which he appeared, he usually poped in towards the end for a surprise twist, in places where he was unexpected. Hearn did not want to relocate to California when Jack moved the radio show to Hollywood, so the character faded out.

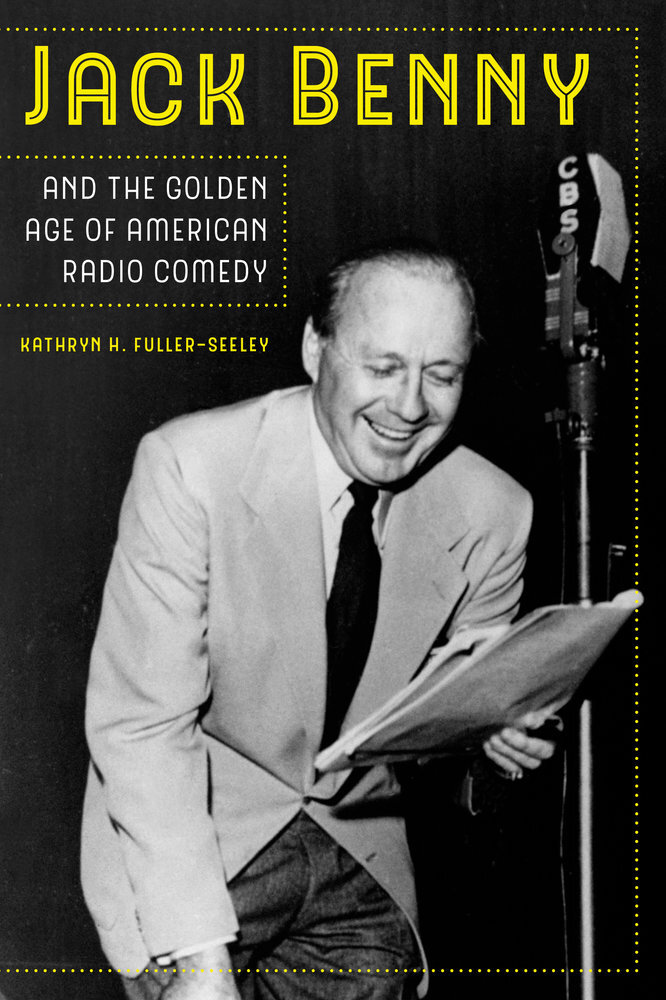

Kathy Fuller-Seeley is the William P. Hobby Centennial Professor of Media Studies in the Radio-TV-Film Department at the University of Texas at Austin; her research specializations are in US radio, film and TV history. Recent publications include: Jack Benny and the Golden Age of American Radio Comedy (California 2017);“Archaeologies of Fandom: Using Historical Methods to Explore Fan Cultures of the Past,” in The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom (Routledge 2018); and (edited) Jack Benny's Lost Radio Broadcasts, Volume One: May 2 - July 27, 1932 (BearManor 2020).

The Mr. Kitzel character was added to the Benny radio program in 1946, a time when interracial and inter-religious tolerance was being promoted by progressive groups. Kitzel was first encountered on the Benny program selling hot dogs in the stands at the Rose Bowl football game. His call of “pickle in the middle and the mustard on top” gained notice in popular culture. Kitzel was the opposite type of character than Shlepperman – a naïve and gentle greenhorn, a barely assimilated Jewish immigrant who constantly misunderstood Anglo American culture and who transposed Anglo names into Yiddish idiom. Jack Benny encounters him in brief interchanges – Kitzel does not become a fully integrated cast member.

Kitzel’s character is similar in ways to Mrs. Pansy Nussbaum, the Jewish housewife character Fred Allen incorporated into his “Allen’s Alley” radio skits from the early 1940s until his radio show ended. Both transpose Anglo-American words and names into Yiddish sound-alikes, in ways that emphasize their lack of American knowledge on the one hand, but I suppose make the listener laugh with kindness and perhaps pity rather than contempt for their lack of understanding. Social critics in the latter 1940s lodged complaints about the stereotypes at play in both these characters, but Allen and Benny both defended their creations, emphasizing their universal humanity and the opportunities they offered to laugh at human frailty.

Henry, you mention Mel Blanc’s characters on the Benny radio and TV program, that’s interesting. Only some of Blanc’s vocal inventions were ethnic characters (I am thinking Polly the Parrot, Carmichael the Bear, the Maxwell’s sputtering engine, the train announcer sending people to Anaheim, Azusa and Cucamonga, the English race horse, etc.). Other characters, however, had strong ethnic identity. Professor Le Blanc the violin teacher shared Jack’s whiteness. However, the Mexican character Mel played, who answered only “Si, Sigh, Sew, and Sue” to Jack’s queries about his family and occupation, have garnered substantial criticism in the years since the skits were aired for their ugly stereotyping (similar to Blanc’s voicing of the Speedy Gonzales in Warner Bros. cartoons of the same era.

Snyder, Robert W. The Voice of the City: Vaudeville and Popular Culture in New York.

Pearse, Holly A. “As Goyish as Lime Jell-O? Jack Benny and the American Construction of Jewishness” Jewish Cultural Studies (2008) 272-290,