What Makes LEGO LEGO?: An Interview with Jonathan Rey Lee (Part Two)

/While the idea of creating a toy for both boys and girlswas part of the brand message from the start, you critique the implicit and explicit construction of gender around the brand. What are the mechanisms by which gender ideologies are structured into the LEGO culture?

This is such an important question! Countless commercial toys are marketed as if children’s gendered differences came already fully formed, although toys absolutely contribute to gendered socialization. Childhood is an incredibly formative time for establishing social identities, so we need to interrogate why our contemporary children’s culture is so strongly gendered. I am no child psychologist so this is a bit of a hot take, but I might go so far as to say that our society will never be able to develop a genuinely equitable gender dynamic without also reimagining children’s culture.

Some of the feminized stereotypes of LEGO Friends on display in a Toys R Us (photo by Jonathan McIntosh).

The most clearly gendered dynamic I explore in the book is the feminized stereotypes of the LEGO Friends product line, which hits pretty much every cliché from the pink-and-purple pastels to the preponderance of fluffy animals and cupcakes. This has drawn a lot of well-deserved criticism from LEGO fans, parents, activists, and scholars, so it’s important to keep digging deeper into how gendered dynamics unfold pretty much anywhere you look with LEGO. Subtle gendered ideologies popped up no matter what I was intending to analyze, often having to do with the masculinization of core aspects of LEGO play (such as the rational organization of suburban spaces in the Town Plan or the action-packed militarized play of LEGO Star Wars).

I also consider how LEGO bodies play with assumptions about embodied gender and how LEGO problematically masculinizes construction play and feminizes social play. This shows that gendering is not just something children bring to toys but is also ideologically infused into the toys themselves. Like many who grew up loving LEGO, I find this deeply disappointing because I personally believe LEGO could appeal to both girls and boys without relying on such reductive stereotypes.

LEGO is often discussed as fostering open-ended creativity and there has been some critique of the rise of playsets, especially those linked to particular media franchises, as scripting children’s play. Yet, you suggest the situation is more complex than this. From the start, you suggest LEGO has been shaped by tensions between “freedom and constraint.” Explain.

This is one of the first things people mention when I talk about the cultural impact of LEGO and it’s easy to see why. Intuitively, a Star Wars playset feels more scripted than a generic space set and a generic space set feels more scripted than a simple box of bricks. This is not wrong per se, but we can nuance this narrative in a few ways.

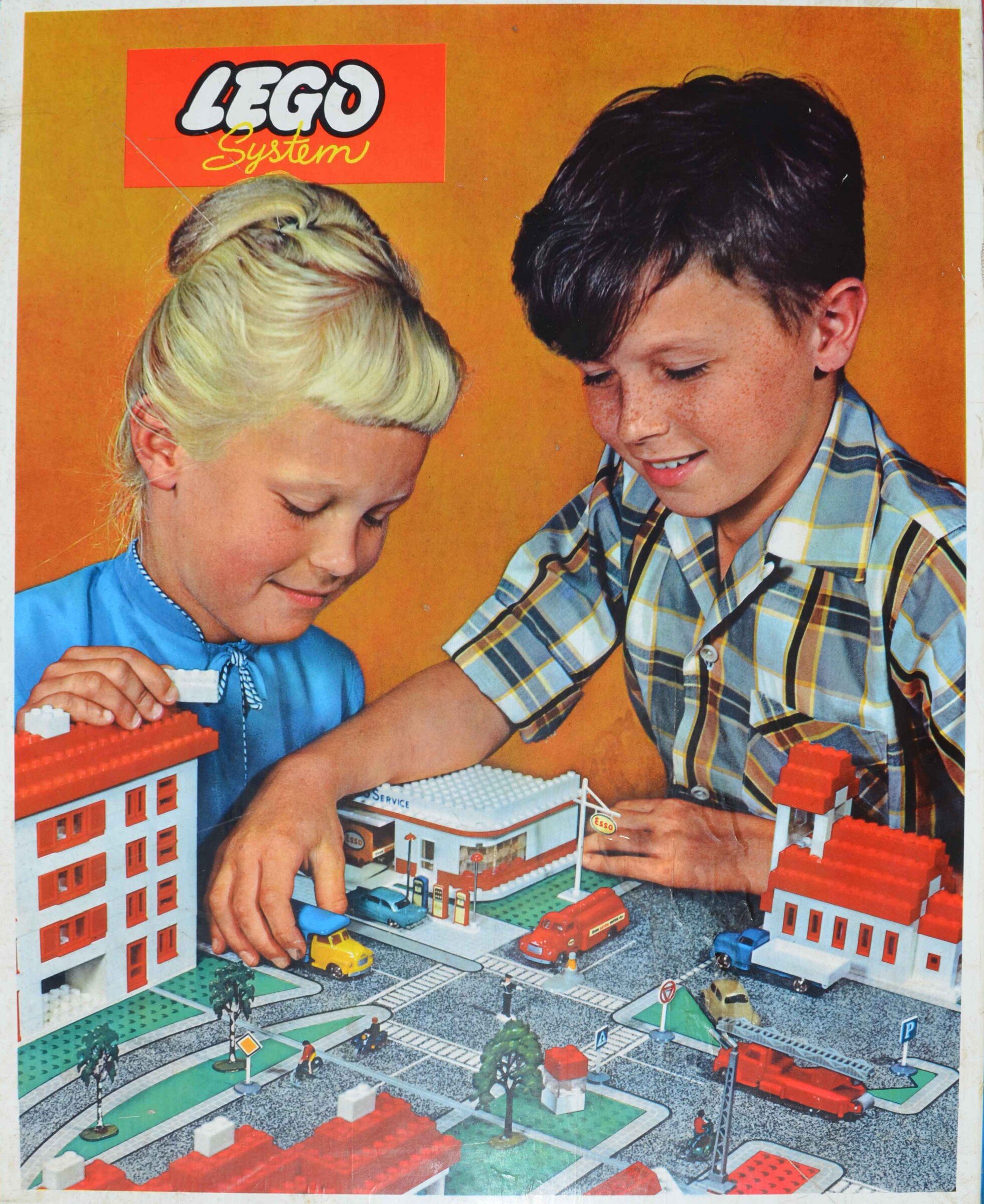

Briefly, the first way to complicate this narrative is to recognize that there was no moment in LEGO history where the system consisted entirely of random abstract blocks. LEGO was always representational, ideological, and socializing. In the book, for instance, I explore how the early Town Plan that popularized LEGO toys was based on a strongly suburban ideology with clear socializing tendencies (brand logos like Esso and Volkswagen appeared on LEGO sets as early as 1956). It’s important to avoid nostalgically overstating early LEGO abstraction in ways that unintentionally make it harder to see and critique the scripts that have accompanied LEGO all along.

This early set from 1961 shows that LEGO was never just abstract blocks. The bricks themselves contain clearly architectural elements and the road signs and Esso logo clearly represent particular cultural institutions.

The second way to complicate this narrative is to see freedom and constraint as two sides of the same coin. LEGO creativity is a form of bricolage, the creative reassembly of already significant elements. LEGO is all about discovering new possibilities within the things you already have, which is to say it’s all about finding freedom in constraints. Every time LEGO weaves a fragment of ideological content into its design, it simultaneously adds to the scripts that constrain play and adds new meaningful elements to play with. In other words, LEGO scripting is inextricable from LEGO’s creative possibility space. So, instead of characterizing constraints as simply limiting creative freedom, this book asks critical questions about how what kinds of ideological entanglements this interplay of freedom and constraint produces.

Your book identifies five “playscripts” surrounding LEGO play, each of which links to larger histories of the logics of children’s play. Can you break these down for us?

If toys are things and play is an activity, playscriptsare explicit messages or implicit norms that suggest how toys are to be played with (Robin Bernstein has done fantastic workon toys as scriptive thingswhere she breaks down this idea in much more detail). Like theatrical scripts, toy playscripts prompt players to play in certain ways while also leaving space for interpretation and expression. Unlike theatrical scripts, toy playscripts tend to be more implicit and function more like ideologies or social norms. In this way, toy playscripts are perhaps closer to improv theater—a set of broad guidelines and constraints for how a scene might play out with a significant degree of freedom in how to reinterpret or reassemble the given elements.The five playscripts I name in this book, which can overlap and combine in interesting ways, are construction play, dramatic play, digital play, transmedia play, and attachment play:

o Construction play is what people might first think of when they think of LEGO: the piecing together of physical bricks into structures. While it’s tempting to think of this physical construction as abstract or neutral, LEGO has been scripting construction play according to an ethos of suburban architectural design that continues to shape the medium.

o Dramatic play is what people might first think when they think of dolls: the puppeteering of characters to dramatize scenes or stories. This involves creatively reassembling fragmented storytelling props to build new scenes. With LEGO, players literally build the stages for their dramatic play, which significantly complicates the scripting of such performances (including adding a problematic gendered dynamic).

o Digital play might make people think first of videogames, but I see digitality as something that bridges material and virtual spaces. This only makes sense if we move beyond only thinking of digitality in terms of the technology involved (videogames use so-called ‘digital’ technology) to the type of thinkinginvolved. So, I look at how all LEGO play—material and virtual—plays with digital ways of thinking, like how discrete, indivisible LEGO elements are pieced together into larger assemblages.

o Transmedia play is an evolution of dramatic play in which the core narrative elements are drawn from licensed media franchises. This is interesting because transmedia play in LEGO usually involves translating narrative media (which tell canonical stories) into playscripts (principles for telling player-created stories) associated with a play medium (LEGO). So, a child playing with LEGO Star Wars may feel pulled simultaneously by the sometimes-conflicting scripts of the source narratives, the LEGO media narratives, and the toys themselves.

o Attachment play is more about the larger cultural idea that playing together is a way to reinforce social bonds. In a sense, the material connectivity of LEGO serves as a metaphor for the social connectivity of people playing with LEGO. I explore this through how the characters in The LEGO Movie and The LEGO Movie 2mediate their relationships primarily through the toy stories they tell with LEGO.

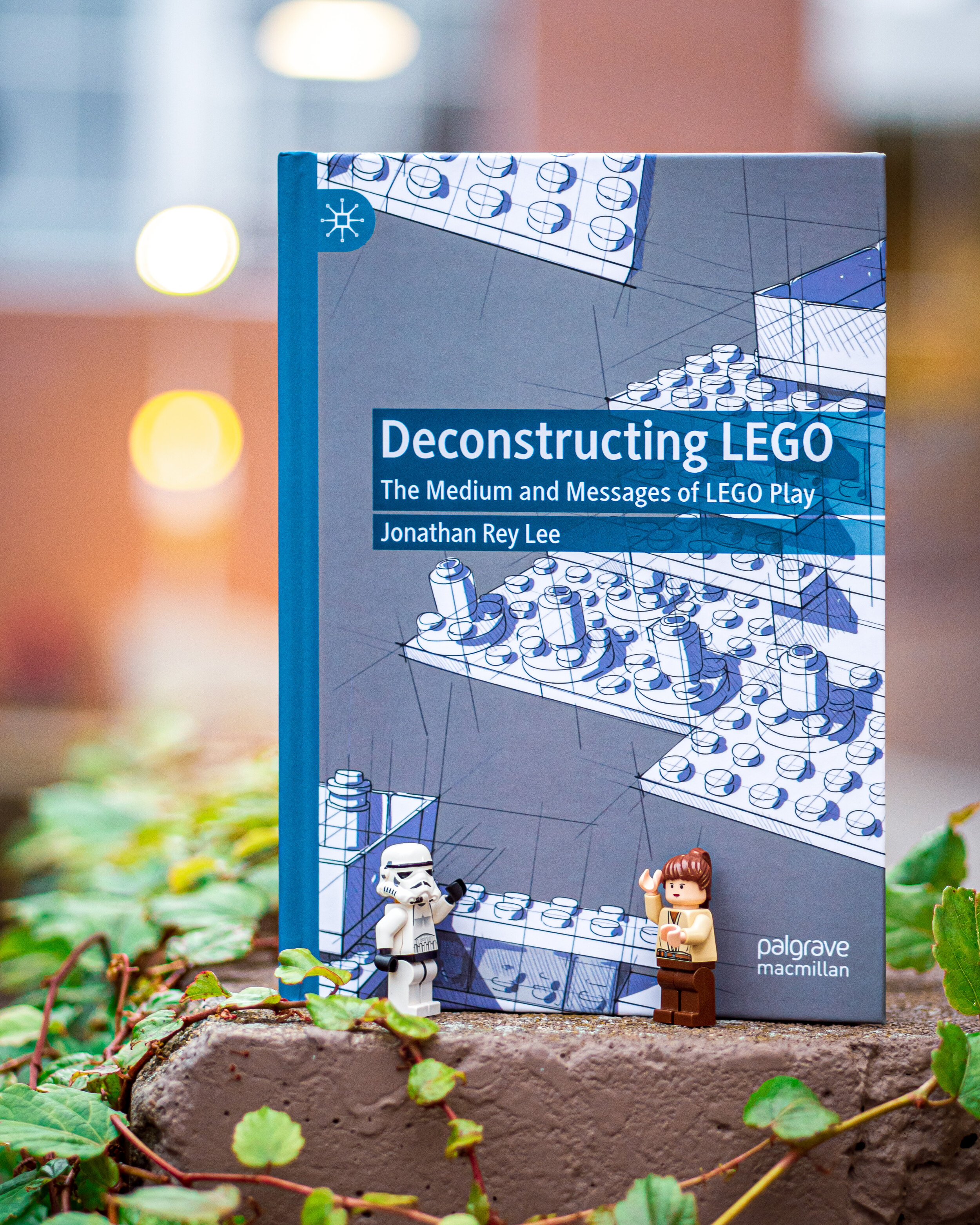

Jonathan Rey Lee researches material play media, especially toys and board games. He has published articles on LEGO, Catan, and the Star Wars CCG. His book Deconstructing LEGO: The Medium and Messages of LEGO Play was published by Palgrave Macmillan in 2020. Jonathan received his Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from UC Riverside, where he studied nineteenth-century realist novels and philosophy (especially Wittgenstein). He currently teaches interdisciplinary humanities and writing courses for the University of Washington and Cascadia College.