Response to Kirsten Pike's response

(by Hyo Jin Kim)

Dear Kirsten and everyone,

Thank you so much for your thoughtful response.

You raised several interesting issues: Korean feminist SF (what the government's scientific discourse is in terms of reaching the public, especially women and girls; how Korean feminist SF expresses Korean sentiment and experiences; what common themes/characteristics of Korean feminist SF are; similarities vs. differences of Korean feminist SF and Western SF; male participants in feminist book clubs), Doctor Who fandom and comparisons with the Scully effect, and the response for the 13th Doctor, Jodie Whittaker.

First, I want to start with some good news and changes in terms of the science culture in South Korea. Since my dissertation, the Korean government and science communicators and experts have reached out to the public for science culture. ‘The Science & Culture Consultative Group’ was established last month, April 2022. This group will work mainly on several missions, such as spreading scientific and cultural activities, designing scientific projects, installing collaborative platforms for developing scientific culture, providing research/suggestions for scientific culture and its policies, filming and producing scientific images and broadcastings, holding academic conferences and seminars, and completing other voluntary scientific and cultural activities. As this group supports and encourages voluntary scientific and cultural activities, it may include some SF fandom activities. I am excited about the group and looking forward to their actions. This group will be the bridge between the public (hopefully include SF fans) and the government in terms of science culture. The government’s efforts in science culture have been accomplished through KOFAC and WISET. The Korea Foundation for the Advancement of Science and Creativity (KOFAC) leads science culture and develops policies as a quasi-governmental and non-profit organization under the Ministry of Science and ICT. In addition, the Korea Foundation for Women in Science, Engineering, and Technology (WISET) is a public institution funded by the government to encourage girls and women in the STEAM (A stands for Art) fields. According to WISET, the gender gap in natural science and engineering has decreased by 1.0% and 10.2%.

Korean SF and especially Korean feminist SF may step ahead of the government's science discourse. Korean feminist SF encourages readers to experience the future and even the current status quo, such as sexist oppression, discrimination, climate change and facing and living with non-human species, including aliens, AI, etc. Korean feminist SF has become more popular with the public since the 2010s. Statistics from the online bookstore ‘Aladin’ show the growth of female readers in their 20s to 40s, as I mentioned in my opening statement. With the reboot of feminism, new young female SF writers such as Cho-Yeop Kim and Se-Rang Chung and their work have become popular with the public. Cho-Yeop Kim won the 43rd Korea Artist Prize with her If We Cannot Move at the Speed of Light (Hubble, 2019) and the 11th Young Writer's Award with her following works. Se-Rang Chung's work School Nurse Ahn Eunyoung (Minumsa, 2015) aired on Netflix's original series in 2020. Media industries also showed interest and started making cinematic dramas such as 'SF8', eight directors with eight original Korean SFs in AI, AR, robot, game, fantasy, horror, supernatural, etc. Now Korean readers and audiences have more chances to meet Korean SF through books and media. The entrance barrier of SF has become lower and easier than before for the public.

As I mentioned in the opening statement, book club participants strongly tied with Korean feminist SF compared to Western SF. One reason might be the Korean storytelling. Participants and the public readers read Korean names, places, and even world views in Korean. They are used to reading characters' Western words and Western world views, making them feel distant from the genre. However, young SF Korean writers' works depict Korean characters (even many Korean female characters, single, married, young, and old) with Korean names, places, and cultures, allowing readers to feel comfortable with Korean SF. Korean feminist SF is mainly concerned with society's various issues and presents many diverse voices of Korean culture. For example, South Korea's constitutional court ordered the law banning abortion must be revised by the end of 2020. It's been 66 years since abortion became illegal. At the end of 2020, several SF writers joined the #abolition of abortion campaign by writing and sharing short SF stories. Korean SF writers openly associate their work with social issues. Korean feminist SF reflects current social issues and lets readers consider what-if situations. Therefore, Korean feminist SF book club participants engage strongly with Korean feminist SF.

Kirsten asked about Korean feminist SF's common themes or characteristics, and I'm working on analyzing and researching as same theme of a book project this year. Fandom research and the sub-genre of feminist SF are rare and getting to start in South Korea. So far, I've seen in Korean feminist SF themes of disability, gender issues, various types of violence toward women and others, stereotypes of women and others, prejudice against women and others, posthuman, patriarchy etc. Analyzing common themes and characteristics of Korean feminist SF is in progress. As a Korean feminist SF reader, I’ve got the impression that every single voice seems to matter to Korean SF writers. Korean feminist SF and Western feminist SF have in common that feminist issues meet the SF genre. Feminist SF writers are actively involved with social issues and let readers find solutions through their imaginations. The difference between Korean feminist SF and Western SF is how feminist issues reflect Korean society. As famous Western feminist SF books have been translated into Korean, readers feel Western feminist SF to be learned rather than empathetic. Every culture deals with different feministic issues. This is why Korean readers get more comfortable and engage tightly with Korean feminist SF. Kirsten wondered if there were male participants in the feminist SF book club. There were no male participants in the "Meet without meeting; 500 days' journey of reading feminist sf" club, but there were some male participants in other feminist SF book clubs I participated. Those male participants had entirely different attitudes toward feministic issues. They joined the book club because they wanted to learn more and understand feministic issues through the book and discussion.

Kirsten asked the Doctor Who fandom about the Scully effect, however, I could not find any academic research in South Korea. SF fandom studies in South Korea are few. In the part of my dissertation, some Whovians learn and understand complicated physics terms through Doctor Who. In my dissertation, I suggested SF fandom as a part of science communication. Scully effect on The X-File seems to follow a similar path, approaching SF fandom as the part of science communication in popular culture. Therefore, finding Scully effect of The X-Files or any other SF in South Korea will be fascinating and could be a good research project for WISET. I was able to find a news article about the fandom of The X-Files. How I remembered The X-Files is unique and different from these days’ SF fandom because of the dubbed version. Kirsten mentioned watching the dubbed version of The X-Files, and there was a massive fanbase surrounding dubbing actors in the '90s PC era in South Korea. There were several fan communities for the dubbing actors and main characters, Mulder and Scully. Still, many fans remember Mulder and Scully as the dubbed version of the voices. One news article shows that The X-Files returned in 2016, and the dubbing actors as Mulder and Scully got the information from the fans and celebrated together. The dubbing actors were as famous and vital as the original actors of Korean The X-Files’ fans. In the '90s in South Korea, I and Korean people were familiar with dubbed versions of television programs such asMacGyver, The X-Files, and other foreign films and television programs. The dubbed actors were top-rated as well. I remember MacGyver's Korean dubbing actor's voice. I was shocked when I heard the actual voice of MacGyver (Richard Dean Anderson). It didn't sound right to me. I am sure this kind of experience is common for people who grew up in the '90s. The popularity and fandom of dubbed versions of films and television programs may differ. Focusing on the differences may present how international fans deal with original characters' voices vs. dubbing actors' voices in a different context. At the same time, the '90s PC era is significant to SF fandom studies in South Korea. That period began with SF fandom, translating Western SFs, and creating Korean SFs. Some current famous SF writers/critics have been actively involved with the '90s PC era since. Several Korean SF scholars consider the '90s PC era a significant time for Korean SF fandom, and research is in progress.

As Kirsten asked about the response of the 13th Doctor, the Jodie Whittaker of Korean Whovians, I would say this might be another good start for the future Doctor Who fandom studies. I was pretty excited about Jodie Whittaker being the 13th Doctor because The Doctor's gender has never been revealed on the show. Though I had to dig deeper for the research, glancing over several Doctor Who online fan communities' comments seem negative responses. As some fans welcomed the female Doctor, they were disappointed with her performance and storytelling. I don't think this is about Jodie Whittaker's performance but fans' frustrations with accepting the female Doctor. The program has run for more than 60 years. Old and even new Whovians are already too familiar with male Doctors. It might take some time to adjust to new perspectives, such as gender or race issues, on the Doctor.

It was an excellent opportunity to learn about Qatar girls’ Disney princess fandom and discuss dubbed versions of films and television programs. It’s been fun to be part of this Global fandom Jamboree Conversation. Always exciting to meet a friendly but inspiring colleague. Thanks again to Kirsten for the thoughtful feedbacks, and hope everyone also enjoyed our conversations.

Part 2: Second Response to Hyo Jin Kim

(by Kirsten Pike)

Thanks so much for your thoughtful reflections, HJ! You’ve raised a lot of excellent points and questions for me to think about. I offer below a few initial thoughts.

With regard to Arab girls creating their own princess-themed media and cultural productions … I, too, was intrigued by this discovery. It immediately brought to mind Henry Jenkins’s pioneering research on female fans of Star Trek, who—in writing new stories about beloved characters—remade popular texts “in their own image, forcing them to respond to their needs and to gratify their desires.”[1] Broadly speaking, the participants in my study tended to create princess-themed narratives that opened up possibilities of greater freedom and independence for girls. And their creations spanned a variety of forms, including songs, videos, games, short stories, photos, and theatrical plays. In a story written as part of a fourth-grade school project, for instance, one participant reimagined Belle from Beauty and the Beast (1991) as a beast, thereby defying customary ideas about how a Disney princess should look and act. Another participant wrote, produced, and starred in a princess-themed play at her high school, which she described as “an Arab version of Cinderella.” However, unlike Disney’s Cinderella (1950), her story challenged gendered conventions in that the heroine—despite being pursued by a prince—opted not to marry so that she could live a more independent existence.[2]

While it’s difficult to pinpoint the precise combination of factors that fostered the girls’ creative (and in some cases, feminist) sensibilities, it’s clear that some participants were encouraged to explore their gendered interests in school-related assignments and activities prior to college. And given that all the girls I interviewed were former students at Northwestern University in Qatar—an American university with staff, faculty, and students from around the world—I think it’s safe to say that they were already interested in and receptive to diverse viewpoints, with childhood influences also surely coming from their family and friends as well as media and other educational/cultural institutions. Indeed, many of the girls I interviewed cited Sheikha Moza, the chairperson of Qatar Foundation (and mother of the current Emir), as a major role model, especially given that her educational initiatives helped international universities come to Qatar, thus paving the way for more young women to earn college degrees here.[3]

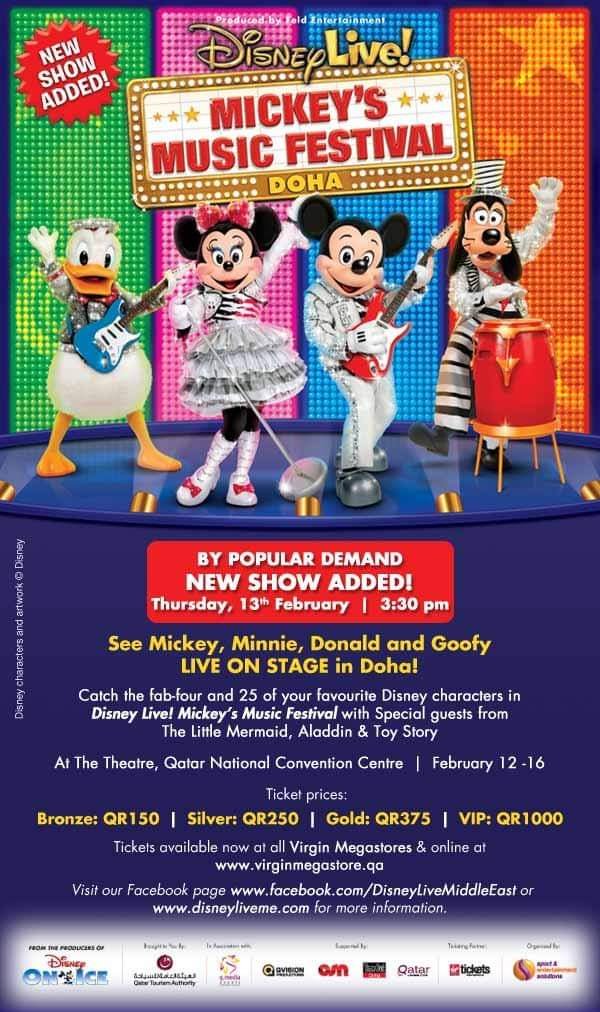

The question of how dubbing informs reception within specific cultural contexts is an interesting one, especially when audiences grow up consuming an eclectic mix of local and global media. In the case of the girls I interviewed, all were fluent in English and Arabic, and they moved easily between Western and Middle Eastern media. Regarding language preferences in Disney media, a few patterns emerged in my findings. First, watching Disney films in English was the preferred mode for girls in my initial study, with ten out of 14 (71%) stating that the original films were their favorite. Some noted that Disney’s English-language releases were the most “authentic” and therefore adored, while others commented that because meaning can be lost in translation, they preferred watching the originals. Four girls in the study (29%) said that they favored the Egyptian-dubbed versions of Disney films because the dialogue, jokes, and/or cultural references were funnier.[4] Interestingly, when eight of the original 14 participants later answered questions about Jeem TV’s local adaptations of Disney films and TV shows (which, beginning in 2013, were dubbed into classical Arabic and edited to be more culturally appropriate for Arab youth), none reported a fondness for these versions. Even though the girls appreciated some of Jeem’s gender-productive editing strategies, including its tendency to eliminate derogatory comments about women and to replace comments about a female character’s looks with remarks about her intelligence, they felt that classical Arabic sounded “too formal” and/or “too serious,” which made them feel distanced from these texts. Ultimately, this discovery highlights the challenges faced by indigenous media producers who strive to create culturally relevant content for local audiences, while also navigating children’s desires for popular global fare.[5]

It was interesting to read your comments about the circulation of Disney content in Korea, including how most parents and young people prefer subtitled rather than Korean-dubbed Disney films because they can help viewers learn English. A few of the girls in my initial study reported that they learned to speak English by watching Disney films and TV shows too. Still, I agree that locally dubbed versions of popular media can have important benefits. One participant in my second study seemed to feel similarly when she suggested that watching Disney programming in classical Arabic on Jeem TV might sharpen Arabic language proficiency among local youth, which some adults fear is in decline because of the country’s rapid globalization over the past fifteen years. However, given the distancing effect described above, perhaps local youth (especially those from the Arab Gulf) would be more receptive to Jeem’s adaptations if they were dubbed in the local khaliji dialect as opposed classical Arabic.

Although my research on Disney fandom in Qatar has so far focused on Arab girls, I agree that it would be fascinating to explore the views of Disney fans living here who come from various racial, ethnic, and national backgrounds. While my chapter “Princess Culture in Qatar” (2015) included an analysis of girls’ responses to portrayals of Middle Eastern characters in Aladdin (1992), it would be interesting for a future study to examine girls’ ideas about representations of race and ethnicity (and their intersections with other markers of identity) across a broader body of Disney princess films, including some of the more recent releases, such as Frozen (2013), Moana (2016), and Frozen II (2019). When I conducted my initial interviews with Arab girls in 2013, a couple of participants talked about how much they admired the more unconventional Disney princesses, including Mulan from Mulan (1998) and Merida from Brave (2012). I would love to find out if, how, and to what extent this interest in non-traditional princesses has evolved with some of Disney’s contemporary releases. And I’d love to learn more about the reception of Disney princess media in South Korea too.

I’m so glad to have had this opportunity to discuss examples of youthful female fandom in Korea and Qatar with you, HJ, as well as to participate in this broader Global Fandom Jamboree. I look forward to seeing how the insights shared via these cross-cultural exchanges over the past few months will continue to evolve and inform our scholarship (and fandom) as time moves forward!

Notes

[1] Jenkins (III), Henry. “Star Trek Rerun, Reread, Rewritten: Fan Writing as Textual Poaching.” Critical Studies in Mass Communication 5.2 (1988): 103.

[2] Pike, Kirsten. “Princess Culture in Qatar: Exploring Princess Media Narratives in the Lives of Arab Female Youth.” In Princess Cultures: Mediating Girls’ Imaginations and Identities, eds. Miriam Forman-Brunell and Rebecca C. Hains, 139-160. New York: Peter Lang, 2015: 154-155.

[3] Arab girls who grow up in Qatar are often encouraged by their families to stay close to home after graduating from high school; Arab males, however, often attend university abroad.

[4] Pike, “Princess Culture in Qatar,” 146.

[5] Pike, Kirsten. “Disney in Doha: Arab Girls Negotiate Global and Local Versions of Disney Media.” Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication 11 (2018): 72-90.