'Misty' and the Horrible Hidden History of British Comics (2 of 3) by Julia Round

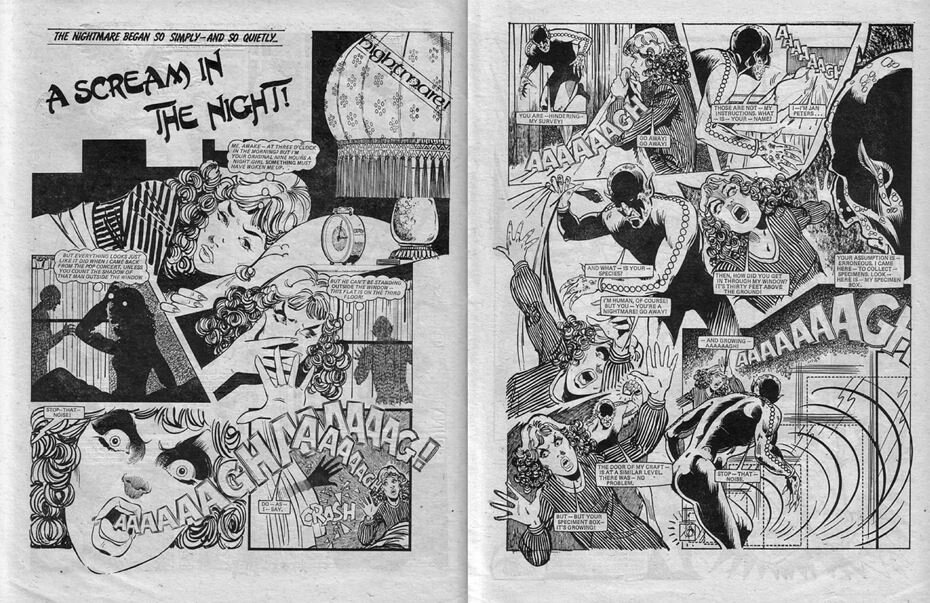

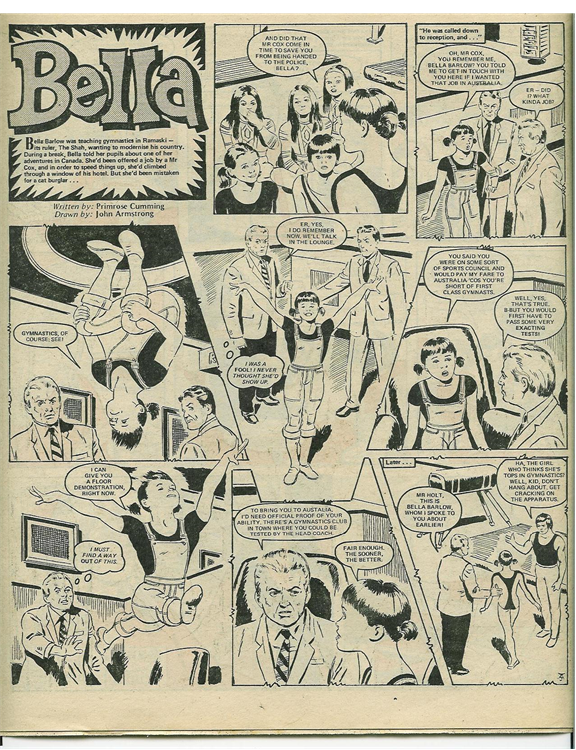

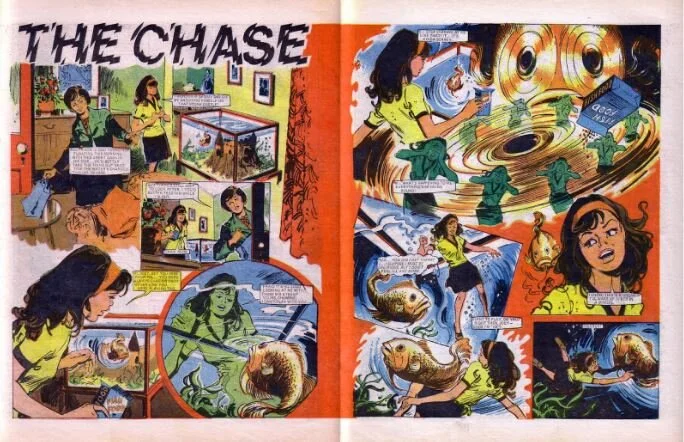

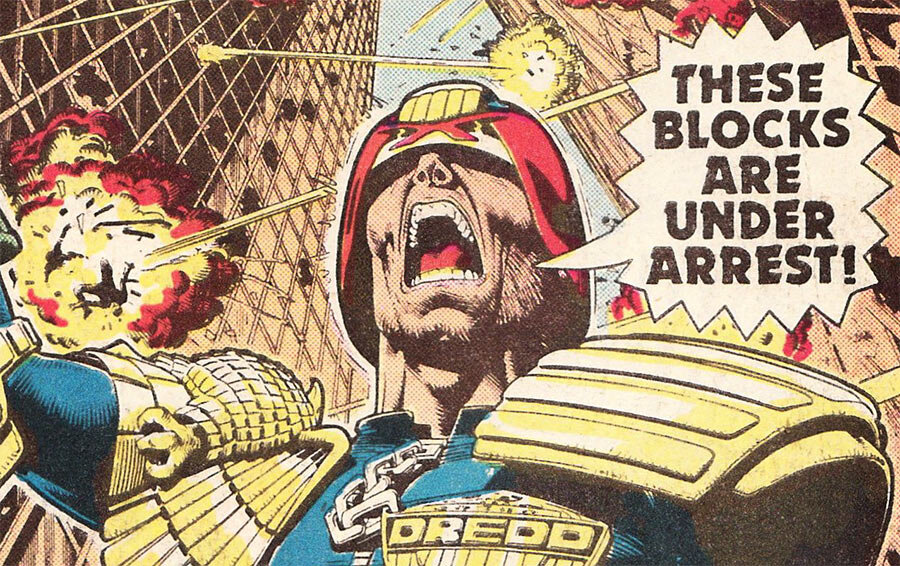

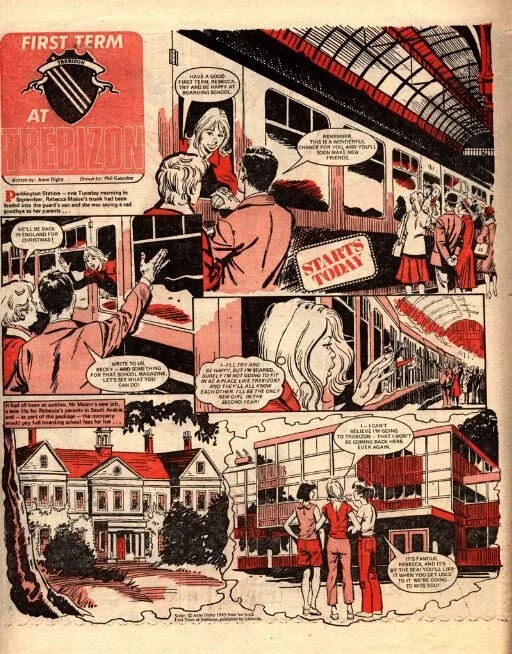

/Unlike other girls’ comics, which would often have a few ‘regular’ serials that lasted for their entire run, such as ‘The Four Marys’ in Bunty (DC Thomson, 1958-2001), Misty kept its serials short (averaging around 10 instalments) and seldom revisited characters. Its serial stories revolve heavily around a mystery theme, and all follow the same rough template as we are introduced to a female protagonist who quickly develops a spooky problem of some kind. This may be the intrusion of a supernatural power (visions, telekinesis, telepathy), or the discovery of a mysterious or magical object (a box of paints, a ring, a mirror, a car, a swimsuit). Alternatively the protagonist may find herself trapped in an unhappy situation (a new family, school or world) or become aware of some deception (a secret prisoner or plot of some kind). The plot then develops as the character discovers new information relating to the item or their situation. One common feature is the focus on a protagonist who has to accept or overcome some aspect of their self, and thus the stories can be read as bildungsroman narratives in which characters negotiate unexpected changes and circumstance (a clear metaphor for adolescence) and ultimately accept their new identity or surroundings. For example, in ‘The Four Faces of Eve’ (Malcolm Shaw and Brian Delaney), Eve has no memories of her past and is plagued by terrifying nightmares of death. She ultimately discovers that she has been made from the bodies of four different girls and is experiencing visions of their memories. The story revolves around her search for a friend (‘I’m so lonely. I’ve got no friends, no memories, and now, it seems, no family!’, #21) and attempts to solve the mystery of her origins. She despairs (‘I’m a freak, a monster!’, #29), but when she finally tells her story to the circus folk she has met, they not only believe her but also show her the way out of her situation, as her friend Carol’s father informally adopts her, saying ‘I’ve got two daughters now.’ (#31)

‘The Four Faces of Eve’, Misty #22. Written by Malcolm Shaw, art by Brian Delaney.

Misty combined these serial instalments with one-off single stories: generally wicked four-page cautionary tales where a delinquent protagonist would be dramatically punished for a misdeed. A short selection might include: Cathy cons an old lady out of a moodstone ring which then sucks all the colour out of her life (‘Moodstone’, #1); a gossip columnist is crushed to death by the books of names and notes she has kept on her acquaintances (‘Sticks and Stones’, #16); clothes-thief Ann is turned into a fashion dummy (‘When the Lights go Out!’, #18); cruel siblings Vivien and Steve trap a mouse in a maze until it dies of exhaustion but are in turn locked in a maze by sentient apes (‘The Pet Shop’, #24); Sally awakens a real ghost while teasing her scared cousin (‘The Last Laugh’, #29); mugger Cath causes an old lady to be hit by a bus but is then run over herself (‘Dead End’, #34); Sue takes a creepy mask to win a Halloween competition but then cannot remove it (‘Mask of Fear’, #39); Rita steals a jigsaw but ends up trapped in one (‘The Final Piece’, #44); Lisa steals a clock but discovers she will have to wind it forever (‘Slave of Time’, #55); Olivia summons the spirits of her teachers to cheat on a test but they will not leave (‘The Disembodied’ #68); cheat Alison is given a magic pen but continues to cheat so it breaks and covers her with irremovable ink (‘A Stain on her Character’, #72); Sally destroys her dad’s snail experiments, but the snails trap and immerse her (‘House of Snails’, #77); Kate scares her little sister with monster stories and is attacked by a monster herself (‘Monster Movie’, #87); vandals break some stained glass windows and end up trapped in the new ones (‘Crystal Clear’, #99); and jealous Roma drugs her cousin and cuts off her beautiful hair, but is then consumed by ghostly hair growing out of the floor (‘Crowning Glory’ #101).

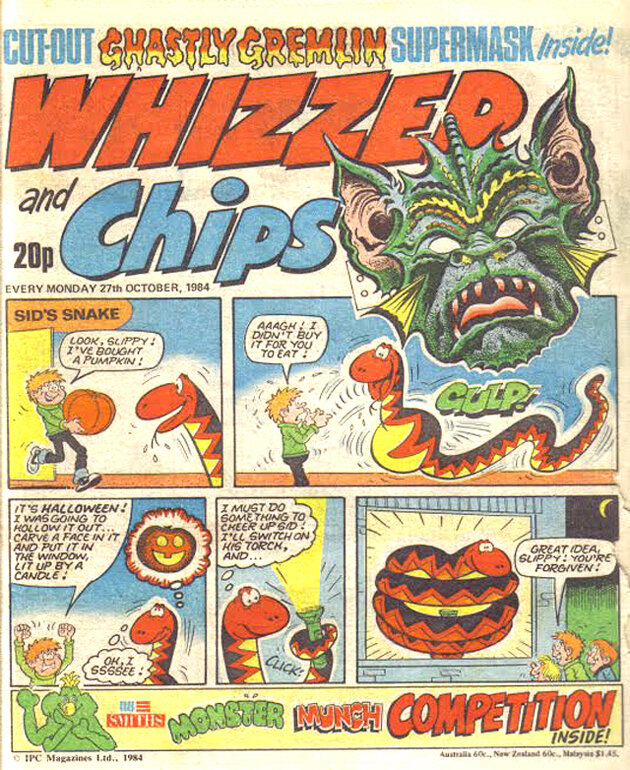

Alongside this were single-page comedy series: Miss T (a hapless witch), Wendy the Witch, and Cilla the Chiller (who appears in the annuals). Miss T was created, written and drawn by Joe Collins, who had created a number of other comedy strips for different titles, such as ‘The Kitty Café Cats’ (Girl), ‘Snoopa’ (Penny, Jinty and Penny), and ‘Edie the Ed’s Niece’ (Tammy). Miss T features regularly in the weekly issues of Misty and even takes over from her on occasion: welcoming the reader on the inside cover (#91) and often appearing and addressing readers on the ‘Write to Misty’ letters page (#16). Her bulging eyes, tangled wiry hair, bulbous nose and warty face should make her a repulsive character, but the little witch exudes innocence and is generally trying to do good (despite unintentional mishaps), making her an appealing heroine. Her battered witch’s hat and oversized shoes also contribute to a visual sense of guileless chaos, and the strip enhances this by being heavy on effects: using emanata such as motion lines, and sound effects (‘Glop’, ‘Burp’). When she is critiqued by a reader in the letters page of #79 (‘I think she’s STUPID and ought to be in stupid comics, not yours’) a lively debate continues for three issues (#89-#91). In the final count Misty claims that 270 people support Miss T with just twenty-six against: ‘a victory for the little witch of more than ten to one’.

‘Miss T’, Misty #70. Written and drawn by Joe Collins.

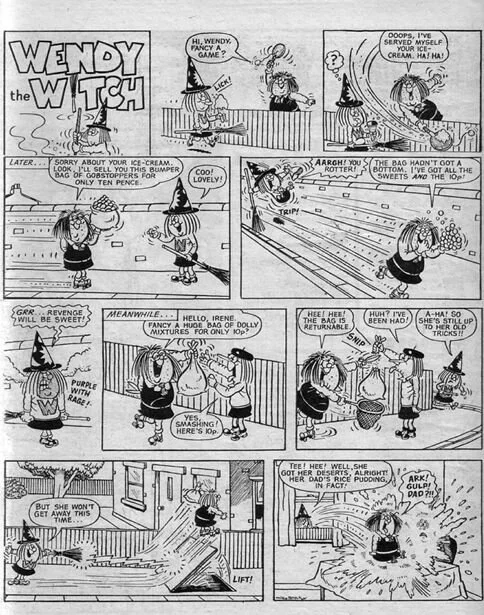

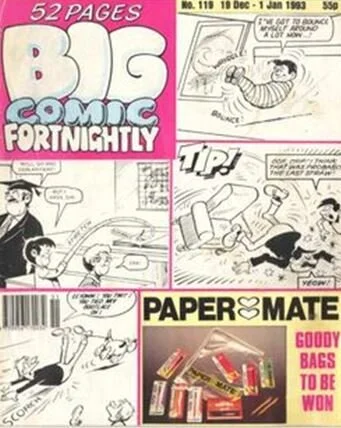

Wendy the Witch (by Mike Brown) was a reprint from Sandie (1972-73), aimed at slightly younger readers. Wendy’s spells often help her to revenge herself on bullies, although they may go awry. Her strips often make heavy use of puns (‘She’s had her chips now, eh, monster?’, #60) and editorial asides. The supporting cast of characters (which include Enid, Nellie, Rosie, and Nosey Nelly) give the strip a feel similar to The Beano’s ‘Bash Street Kids’ (Leo Baxendale), or ‘Dennis the Menace’ (devised by George Moonie, David Law and Ian Chisholm) as Wendy gets ‘the slipper’ from her mum (Misty Annual 1979).

Cilla the Chiller, a schoolgirl ghost who haunts a stately home and plays tricks on its visitors, appears only in the Misty annuals. Its creators are unknown, and the strip has a similar feel to the other two comedies: puns are common, and the art is in a typical British comics style: reminiscent of the work of Reg Partlett or Leo Baxendale.

‘Wendy the Witch’, Misty #55. Art by Mike Brown.

Julia Round’s research examines the intersections of Gothic, comics and children’s literature. Her books include Gothic for Girls: Misty and British Comics (2019), Gothic in Comics and Graphic Novels: A Critical Approach (2014), and the co-edited collection Real Lives Celebrity Stories. She is a Principal Lecturer at Bournemouth University, co-editor of Studies in Comics journal (Intellect) and the book series Encapsulations (University of Nebraska Press), and co-organiser of the annual International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference (IGNCC). Her new book on Gothic for Girls and Misty is accompanied by a searchable database, creator interviews, and other open access notes and resources, available at www.juliaround.com.