Youth Power in Precarious Times: Interview with Melissa Brough (Part One)

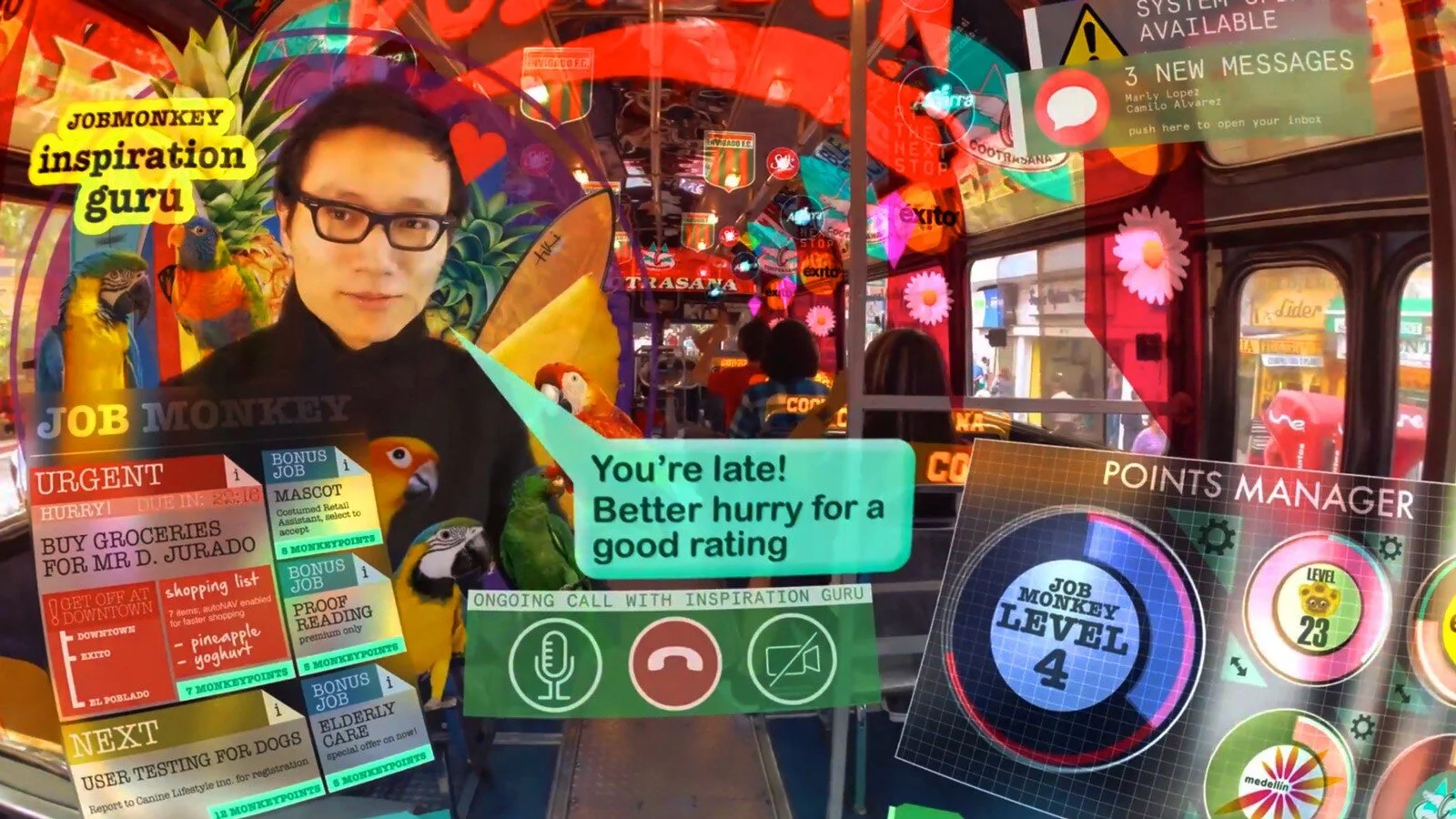

/When I first came to USC more than 11 years ago, one of the first students I met was Melissa Brough, who challenged me to rethink some core assumptions about participatory culture by calling my attention to critical writings from Latin America. Through the years since, she has continued to hold my feet to the fire. She wrote a brilliant dissertation growing out of the field work she had done with various youth initiatives in Medellín, Colombia. She managed to deftly thread the needle with a committee which included myself, Manuel Castells, Sarah Banet-Weiser and others. She wrote a really provocative overview of various forms of fan activism with Sangita Shresthova for Transformative Works and Cultures.

And now she has published her first book coming out of this research, Youth Power in Precarious Times: Rethinking Civic Participation. This work merges a deep theoretical engagement with multiple traditions of writing about participation with some substantive observations from the field considering why these theories matter in terms of their application to the problems confronting the Global South. Any of us writing about participatory culture, learning, and politics need to engage seriously with this book. This interview will give you a preview of what you will find there.

From the start, you have described your project in terms of an effort to bridge between debates concerning participation as it has been framed in the “global north” and the “global north.” What can you tell us about the historic debates around participation, particularly youth participation, in Latin America?

In 2000 I spent a summer working with the Chiapas Media Project (CMP), a video project in Southern Mexico that helped train indigenous communities to produce their own videos, often in association with the Zapatista movement. The CMP was just shifting from linear to non-linear digital editing at that time, and I had the great privilege of teaching their indigenous filmmakers how to edit in Final Cut Pro. In the process, they taught me about a totally different style of video production than what I’d been taught in school; one that prioritized the needs of the community through a collectivist, collaborative process of video making. I ended up writing my undergraduate thesis about this project, and in so doing was introduced to decades of literature and case studies in participatory communication. So my first exposure to the idea of participatory media was not Web 2.0; it was participatory media as it had been practiced for decades across Latin America.

(Photo thanks to Chiapas Media Project)

Latin American theorists, practitioners and researchers of community participation have really been at the forefront of this topic for decades, at least as far back as the Bolivian miners’ network of radio stations founded in 1949, which were initiated, owned, and operated by and for local community members to share information. Since then, many cases of participatory media, theater, etc. have been documented across Latin America and beyond; see, for example, Making Waves: Stories of Participatory Communication for Social Change. The field of Development Studies has done a better job to date of incorporating this body of knowledge and practice than have Media or Communication Studies. This is in part because Development Studies is primarily focused (for better or worse) on the so-called global South, whereas these other fields of study are typically very Western and Northern-centric. One of my motivations for doing this study was to try to push back against the dominant flow of information and scholarship from the global North to the global South and draw attention to these rich histories of participatory media, culture, and communication that most of the scholars in the U.S. were not aware of or acknowledging at the time.

Colombia in particular has been a nexus of participatory communication and other participatory projects for decades. I discuss this in Chapter 2 and elsewhere in my book, but Clemencia Rodriguez’s book Citizens’ Media Against Armed Conflict: Disrupting Violence in Colombia is another fascinating study of the rich fabric of citizens’ media and their wide range participatory practices in Colombia. (Note that both Rodriguez and I use the term “citizen” broadly, not confined to the legal status conferred by nation-states.) Pilar Riaño’s edited volume Women in Grassroots Communication: Furthering Social Change was also influential for me, along with the work of Paulo Freire, Robert Huesca, Alfonso Gumucio Dagron, Orlando Fals Borda, and many others. (For interested readers, several relevant texts are gathered in the Communication for Social Change Anthology compiled by Alfonso Gumucio Dagron and Thomas Tufte.) Freire, a Brazilian educator and philosopher most well known for his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed (1970), is widely considered one of the most important theorists of participation of the 20th century. He described participation as being “an exercise in voice, in having voice, in involvement, in decision making at certain levels of power... a right of citizenship.” His work continues to influence participatory projects in Latin America and beyond.

In terms of youth participation in particular, two of my favorite Latin American scholars are Rossana Reguillo (especially Culturas Juveniles) and Ángela Garcés Montoya (especially Nos-otros los Jóvenes). They both take the cultural and political work of young people seriously, and illuminate how power is struggled over and wielded through symbolic, cultural forms. But I learned the most by observing and collaborating with youth activists and artists in Medellín. It was their work, and their thinking, that led me to the insights offered in my book.

As you note, “While some scholars suggest that participation has been rendered a nearly useless concept with its widespread proliferation and should perhaps be abandoned, this book contends that it is crucial to recuperate its analytical and practical utility in order to work towards more equitable, just societies.” Explain. Why do you see participation as an especially valuable concept in this context? What work needs to be done to reclaim and redefine it?

In many ways, participation in public life seems more critical but also more complicated than ever. Traditional civic and political institutions have been largely discredited, particularly among younger generations who do not see their identities and needs reflected in these institutions, and who enact their political will in non-traditional ways (much of which you and your team has been documenting for some time now). This disconnection between young people and traditional institutions has been well documented in many parts of the globe, including in Latin America. The dynamic of disconnection has been further exacerbated by a fragmented mediascape and the variously construed phenomenon of “fake news”.

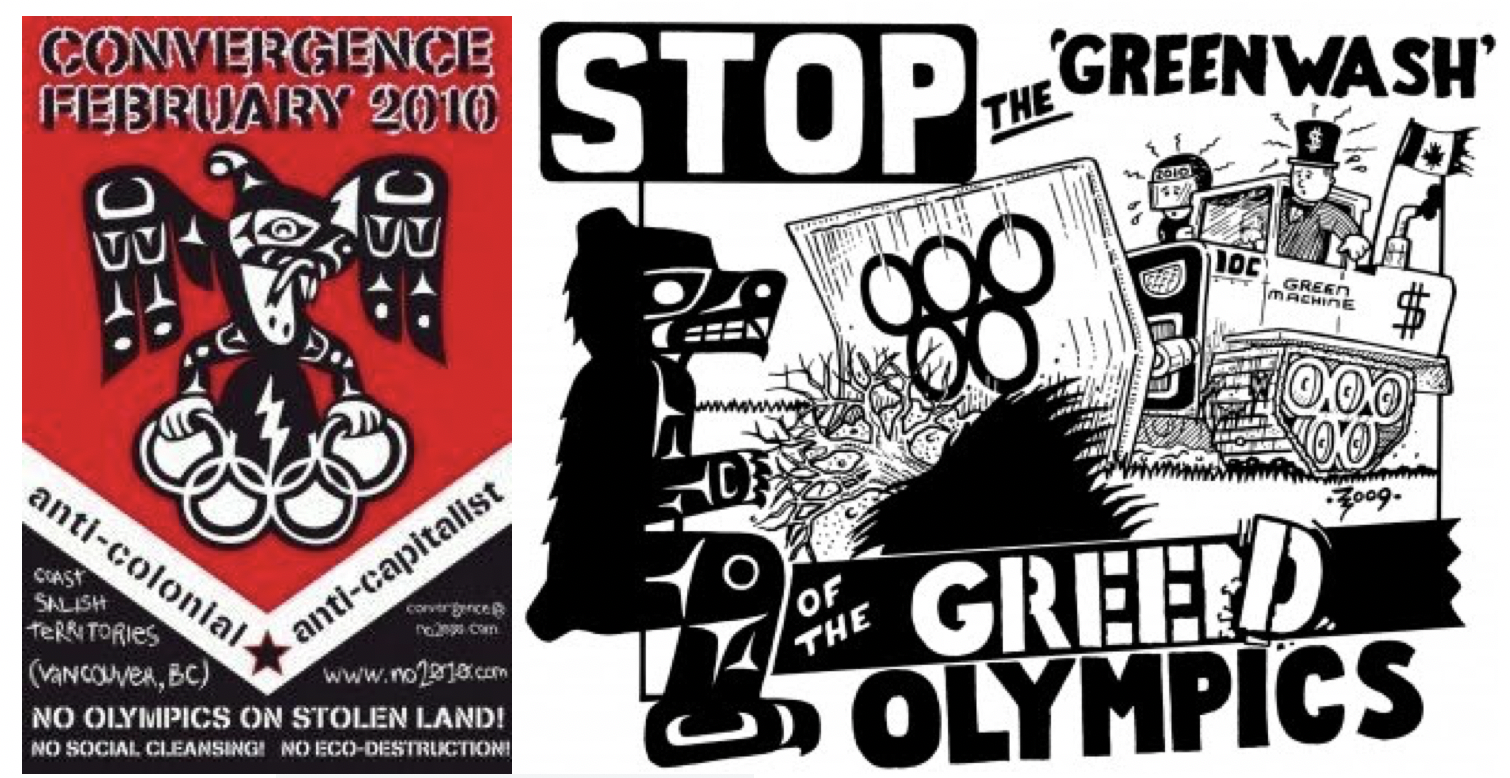

With the rise of Web 2.0 discourses of participation in the global North went from being relatively fringe and often counter-hegemonic to being fully mainstreamed and commercialized. There are so many examples of this; one I find particularly relevant and darkly amusing is Flock Associates’ description of Mountain Dew’s “Dewmocracy” participatory marketing campaign. (Here’s a taste: “We proposed that the brand give the people their due [Dew?]—it was to be the ultimate Dewmocracy... with the ultimate goal of creating an elixir that will restore choice to the people. [Online game] players worked together to design the color, flavor, and feel of their elixir that will ultimately become the next Mountain Dew product... The people’s voices were heard... [bringing] forth on this continent a new Dew, conceived in liberty.”) It’s no wonder that the commercialization of the rhetoric of participation left a bitter taste in the mouths of those who had been advocating for more participatory democracy for decades; if the rhetoric of participation can be so easily and completely co-opted to sell soda, how useful is the concept anymore? And yet the de-popularization and delegitimization of traditional government and civic institutions -- and, crucially, the press -- is clearly benefiting only a very small number of traditional power holders.

Participation never has been and never will be perfect. Participation is messy. Practitioners and researchers in international development have perhaps best documented both the promises and perils of participatory practices for community building, development, and empowerment. They’ve shown inefficiencies, inequalities, and corruption in processes of participation that were meant to promote democratic practices (see, for example, Cooke & Kothari’s collection, Participation: The New Tyranny?); I found instances of all of these in Medellín. You obviously cannot have a democracy without participation; but participation does not a democracy make. One of the arguments of my book is that it’s time to reclaim and redefine participation so that it can be demanded, enacted, grappled with, and improved. In this book I focus specifically on participation in civic and political life and define participatory public culture as one with “significant opportunities for horizontal decision making, based in practices of dialogic communication with low barriers to participation, through which issues of public consequence are negotiated. A participatory public culture is one in which the voices, interests, and participation of non-hegemonic groups are valued.” This definition articulates some of the key characteristics of a public culture that offers meaningful opportunities for participation. While I believe this definition is more specific and therefore more useful than the vague and sweeping ways in which participation is often talked about in the current moment, I also believe that participation is a concept that must continuously be interrogated, refined, and redefined to better account for how relations of power are enacted in and through it, and to take contextual and historical factors into account.

One of the biggest lessons I learned from the case of Medellín is that if we think about and support participation ecologically, from grassroots youth activists to civil society organizations to local and state government and beyond -- and, crucially, the relationships between these -- we have a better chance of nurturing a functional, vibrant, and democratic public life. This is why I make the case for polycultural civics. Borrowing the concept from agriculture, polyculture (vs. monoculture) refers to the practice of cultivating different crops in the same space in a way that is mutually beneficial and enhances the overall ecosystem. I adapt it here to think about participation as a resource that can be cultivated in different ways at multiple levels, from the grassroots to institutions -- and to emphasize that the relationships between these are crucial.

What happened in Medellín from 2004-2011 is that many actors in the “ecosystem” of Medellín’s public life began working together in mutually beneficial relationships, even if sometimes their agendas were in conflict or competition. For example, the municipal government created a participatory budgeting process that enabled citizens age 14 and above to participate in the allocation of 5% of the city’s annual budget. The process was not perfect, and went through several iterations. People and organizations competed for the resources. Yet, at the time of my research, the outcomes of the participatory budgeting process for communities throughout the city were largely positive -- particularly so for youth (as young as age 14), who were quite active in the process.

That is not to say the participatory budgeting process wasn’t flawed and susceptible to manipulation by corrupt actors -- it certainly was. And it only accounted for a small percentage of the city’s overall budget. But the predominant impact of this ecosystem of participation was to increase the opportunities for citizens (especially youth, women, and other groups who were traditionally marginalized from city politics) to participate meaningfully in public life. In the process, citizens learned how to engage actively and effectively in the development and governance of their communities. It was an especially powerful civic and political education for youth, who were learning by doing. At the same time, the local government gained greater legitimacy locally and internationally. This was a polycultural relationship. And within it, the concept of participation was defined, contested, debated, and refined in the process. This is an example of how participation is contextually and historically contingent; it is shaped within particular contexts, practices, relationships, and histories.

So one of our key tasks is to be historically and contextually specific when we talk about participation -- with special attention to who gets to participate, how, who is defining the terms of participation, who benefits from the participation, who wields power within (and after) the process of participation, and what is the labor involved in participating. I’m writing this just weeks away from the U.S. presidential election, the day after the New York Times released information about Donald Trump’s tax returns. I am reminded to add the question, who doesn’t participate?, and what are the costs of that to an ostensibly democratic society?

Melissa Brough is Assistant Professor of Communication & Technology in the Department of Communication Studies at California State University Northridge. Her research focuses on the relationships between digital communication, civic/political engagement and social change. Much of her work considers the role of communication technology in the social, cultural, and political lives of youth from historically disenfranchised groups. Her research has been published in Social Media + Society, Mobile Media and Communication, the International Journal of Communication, and the Johns Hopkins Guide to Digital Media, among others. Her first book, Youth Participation in Precarious Times: The Power of Polycultural Civics (2020), is now available from Duke University Press.

For more information, and to order the book directly from Duke University Press at a 30% discount please visit Youth Power in Precarious Times: Reimagining Civic Participation and enter the coupon code E20BROGH at checkout.