Cult Conversations: Interview with Mark Bernard (Part II)

/In Selling the Splat Pack, you discuss the way in which the DVD produces a “super text.” Can you explain what you mean by “super text” in this context?

For me, the idea of “super text” was my adaptation of Catherine Grant’s notion of the primary text – that is, the feature film – and secondary texts – the extra features – on a DVD blending to the point where they all make up what she calls “the story of the film.” So, in the case of Splat Pack auteurs like Eli Roth and Rob Zombie, their films on DVD blur into the secondary materials to the point where the story of the film is just as significant – or more important – than the story told by the film. For example, I’d say that the story of the Hostel films is ultimately a story about Eli Roth attempting to craft and sell an image of himself as a provocative horror auteur. Taken on its own, the film The Devil’s Rejects may be a film about the revenge of the underclass and/or a return to the “urbanoia” film, but as it appears on DVD with all the extras grafted onto it, the story of The Devil’s Rejects is one about the slippage of identity and a type of cross-class spectatorship. The “super text” of Saw is that of a dark, demented theme park, which is fitting considering that Saw is the only horror franchise – to my knowledge at least – that has been adapted into a roller coaster.

One of the fascinating arguments in Selling the Splat Pack is the idea that directors such as Eli Roth and Rob Zombie “utilize the DVD platform to frame their films in a wide variety of ways” (142). What did you discover regarding such paratextual frames and what purpose do you think they serve?

They serve different purposes for different directors, I believe, and Eli Roth and Rob Zombie are two good examples. I believe Roth used the paratextual frames afforded by DVD to do a couple of things. One, I believe he attempted to immediately canonize himself as a significant horror director. He was certainly not shy when it came to promoting himself. This is likely the reason that some folks found him a bit grating. As for myself, I didn’t write about him to praise or damn him. I just found it fascinating that DVD, as an industrial practice and a consumer product, gave this budding auteur a way to promote himself as a premier genre director. At one point I cited Timothy Corrigan’s claim that Quentin Tarantino was an auteur for the VHS age. I saw Roth as the DVD corollary. And it just so happened that Tarantino was Roth’s mentor.

Secondly, Roth used DVD as a way to position himself as a political filmmaker. Roth seemed enamoured with the image of a “serious” and “political” horror filmmaker like George Romero. Joe Tompkins, in his great chapter for Merchants of Menace, wrote about this as well, this sort of valorisation of figures like Romero that makes them into not just cult figures but almost folk heroes and how horror filmmakers attempt to evoke these figures to distinguish themselves. I believe Roth saw DVD as a way to build a reputation for himself as a serious filmmaker in this mould. Roth was obviously aware of various discourses – some of these “reflectionist” interpretations coming from academia – that read Romero’s films (and the films by other directors like Wes Craven and Larry Cohen) as actually being about the Vietnam war and the counterculture moment. Roth attempted to channel the Iraq war and the debates about torture through his films. Sometimes his allusions came across a little ham-handedly in his films; sometimes, I don’t believe they came through at all. However, DVD gave Roth multiple opportunities to tell any viewer willing to listen that this subtext was indeed there and to use this subversive veneer as a way to sell his films.

I believe Roth just legitimately loves horror cinema, and the DVD extras allowed him a lot of opportunities to talk about horror. As he says on one of the commentary tracks on the Hostel DVD, “I’ve got a lot to say. It’s hard to shut me up, especially when I’m talking about horror movies.” Using Catherine Grant’s perspective, I’d say the “story of the film” when it comes to the Hostel films on DVD is the story of Roth positioning himself as a significant auteur, a political filmmaker, and a horror fan.

The paratextual materials play a similar role when it comes to Rob Zombie’s films. However, there’s a key difference between Roth and Zombie: while Roth sells himself as a political filmmaker, Zombie doesn’t seem to care very much about politics or being seen as political. I believe the “behind-the-scenes” features on Zombie’s DVD foreground his seriousness as a filmmaker and his meticulous nature. It could have been easy for some to write off Zombie as a vapid director of the “MTV” stripe Zombie since he was coming off a career as a heavy metal musician. But the paratexts showcase the seriousness and artistry that Zombie puts into his films in immense detail. I mean, the “making-of” documentaries on both The Devil’s Rejects DVD and the Halloween remake DVD are both longer than the films themselves. I argue that these paratexts also show Zombie’s fascination – which seems sincere – with acting. He seems enamoured with actors. He is married to one after all, so I guess that makes sense! The process of acting also seems to fascinate him, which is interesting considering the play of identity that I see as integral to his films and their appeal. I believe this is one of many points where the division between primary text (the film) and secondary texts (the extras) begins to blur, making the “story of” Zombie’s films one about the slippage of identity.

It is fascinating that directors seem to be aiming to legitimate horror as an art form through a kind of producorial paratextual politicisation. Do you think this is because horror remains critically disparaged in academic and press circles, and as a consequence, filmmakers, such as the ones you analyse in Selling the Splat Pack, aim to discursively politicize horror cinema as a method of redressing said disparagement?

First, I must say: “producorial paratextual politicisation” is an amazing term! This process is most definitely at work, especially when it comes to Eli Roth.

I’m not certain I would agree that horror is totally disparaged in academic circles. Actually, I believe horror has perhaps fared much better in academic circles than in the popular press. Studies of horror cinema have been around since the institutionalisation of film studies as an academic discipline. It’s possible one could argue that much scholarship on horror cinema resulted because the genre just happened to pair well with psychoanalytic approaches that dominated film studies throughout the 1970s and 80s. This could have been a factor, but nearly every horror film scholar I’ve read is an admirer of the genre. Horror has its own academic journal, something that other genres cannot boast. I believe horror has done pretty well in academia.

But it is certainly true that horror has not done so well in popular circles and has remained disreputable among most critics.

What I believe directors like Roth were trying to do is take discourse from academic studies of horror – studies that noticed the genre’s subversive potential – and use it to, as you put it, redress critical disparagement of horror. On one level, I believe that’s great. As an admirer of horror cinema, I’m happy to see filmmakers defend horror cinema and proudly claim that their films are horror rather than do this tap dance that filmmakers often do in interviews and publicity where they’re hesitant to identify their films as horror. For instance, I loved the film Hereditary, but it is frustrating to read or watch interviews with Ari Aster, the writer/director, and see him waffling back and forth about how his film is a horror film, but at the same time, equivocating that it’s more of a “family drama” or “domestic melodrama” than horror. It’s tiresome.

At the same time, however, it can be a bit grating when filmmakers openly declare their film is horror, but use topicality – often bastardized from academic “reflectionist” approaches that are flimsy to begin with – to justify their film’s status as horror. In other words, saying things like “this is horror film, but it’s actually about the Iraq war” or something of that sort and using that to sell the film is almost as bad as the tap dance approach because there’s still the inference that horror cannot stand on its own. It always has to be “about” something to be worthwhile. That’s irksome for me. It’s also frustrating when this type of discourse is commodified, as I argue in Selling the Splat Pack.

In a recent BBC News article, Anne Bilson argued that: “Whenever a horror movie makes a splash... there is invariably an article calling it ‘smart’ or ‘elevated’ or ‘art house’ horror. They hate horror SO MUCH they have to frame its hits as something else.” How would you respond to this statement?

I believe Bilson is absolutely right. All this talk about “post-horror” is predicated on the idea that horror in and of itself is not “good” enough to warrant any consideration or analysis, which I, of course, do not believe.

This idea bugs me for a couple of reasons. First, in terms of my own personal approach to film analysis, I don’t believe it’s my job to say if one film is “better” or “worse” than another. Like, is A Quiet Place “better” than Paranormal Activity 4? Is Get Out “better” than Happy Death Day? I honestly don’t care that much. I don’t look at horror films in terms of “better” or “worse.” For me, horror films exist on a spectrum. They aim to deliver different experiences to different types of audiences. That sounds like an obvious observation and maybe it is, but for me, it’s important.

But, just for the sake of argument, if folks want to talk about recent critically-acclaimed horror films being “better” than past genre outings, it seems to me that is worth looking into the industrial/historical context from which these films are emerging. If we are indeed seeing the release of “better” or “higher quality” horror, what changes in the film/media business may have been a catalyst for this shift? That’s a much more interesting question for me that I haven’t seen discussed as much. I was very intrigued to see, in the Nicholas Barber article for BBC, that “elevated horror” apparently was a term being tossed around by Hollywood executives as far back as 2012. I’d like for someone to look into that a bit more and examine the commercial imperatives behind these “post-horror” films.

In the US, movie attendance is bottoming out. Since the market is shrinking and making movies is such a precarious enterprise, we’re seeing a couple of things happen. On the more expensive end, majors are relying more and more on franchises and recognizable brand names. Beyond that, a lot of the smart money is withdrawing from the theatrical market and focusing instead on producing original content for television and streaming services. This seems to have left space in the theatrical market for different, more diverse films with low-to-moderate budgets. Horror remains a reliable genre, so maybe it makes sense that financers and distributors might look for projects that combine a reliable genre with fresh takes from adventurous filmmakers, including women and people of color. I believe that’s how you end up with films like The Babadook, The Witch, Get Out, and Hereditary.

Mind you, these are all just armchair observations. I haven’t researched any of this, and this is just supposition. But it seems to me that the industrial side of all this is worth a closer look.

What are your plans for the future in scholarly terms?

At the moment, I’m desperately trying to finish up a monograph about John Carpenter’s Halloween for Routledge’s Cinema and Youth Cultures series. It’s a short book, but it’s been a tough one. Writing about the film is a bit intimating for me because it’s such a classic and so much great stuff – both academic and popular – has been written about it. But I believe there’s still some new ground there to be covered, and I hope I cover it in a useful way.

After that, I’m not certain. I have a couple of dream projects I’d love to do if I ever have the time and resources, but I’m buried under student papers for the foreseeable future!

And finally, what five films would you recommend that you feel represents ‘the best’ that horror/ cult cinema can offer and why?

Freaks (Tod Browning, 1932)

For me, this is the textbook example of a cult film. Every stage of this film’s life – from pre-production to its remediation in a multitude of reception contexts – is fascinating. Looking to outdo the success of Universal’s Dracula and Frankenstein, Irving Thalberg, the head of production at MGM, sought to make the ultimate horror picture, and Tod Browning, former sideshow carnie and director of some of the most macabre mutilation melodramas of the 1920s, gave him this film, which scandalized audiences by featuring actual sideshow “freaks.” One of the most fascinating aspects of this film is that, up until the last ten minutes or so, it’s not really a horror film at all. It’s made up mostly of “slice-of-life” vignettes about working in a traveling circus sideshow. Characters fall in love, break up, have children, and get into arguments with their co-workers about common, everyday things. It just so happens that most of these characters are played by people of extreme bodily difference. The scene in the middle of the film when Hans tells Frieda that he plans to marry Cleopatra is so syrupy and melodramatic, but when the typical viewer takes a step back and reminds themselves they are watching this soap opera scene play out between two little people, the viewing experience is often one of ambivalence, which is both discomforting and engaging in a way few other films are. When the film takes a dark turn in its final act and these “Othered” characters that have been so humanized throughout the film begin to act in monstrous ways, it’s even more unsettling. The horror film theatrics of the climactic scene – the dark night, pouring rain, flashing lighting, booming thunder, and the sight of the “freaks” crawling through the mud toward their victim – are indelible. The film is barely over an hour long, but the emotional journey on which the film takes the reader seems much longer. There’s simply not another film like Freaks.

Bride of Frankenstein (James Whale, 1935)

They say that sequels can never surpass the original, but this film proves that old cliché to be dead wrong. The first Frankenstein film was a smash success for Universal Pictures in 1931. By all accounts, James Whale, the director of the film, did not want to direct a sequel and agreed to do so only if he could bring his own distinct flavour to the proceedings. The result is a film that demonstrates how the dialectic between Hollywood convention and the idiosyncrasies of a distinctive filmmaker can produce a cultural artefact that’s defiantly heterogeneous. It feels like three different films sewn and stitched together, like Frankenstein’s monster. There’s the tale of the creature, who is the prototype of the sympathetic monster; then there’s Henry Frankenstein, the creature’s creator, who epitomizes the tortured soul who cannot help but give into his sinister, unnatural impulse to make monsters; and then there’s the flamboyantly camp mad scientist Septimus Pretorius, a devilish figure who tempts Henry away from the straight and narrow down a deviant path. Everything great about the Hollywood horror film is here, from gothic iconography of castles and forests, to shadowy cinematography, to psycho-sexual subtext. Also great is Franz Waxman’s score, with leitmotifs that signal the presence of the film’s three monsters: Pretorius, the creature, and the creature’s bride.

The Masque of the Red Death (Roger Corman, 1964)

Roger Corman’s Poe adaptations starting Vincent Price are essential viewing for any horror fan. I love all of Corman’s Poe movies, but this one is my favourite, just barely edging out The Pit and the Pendulum. Part of what makes Masque so great are the elements it shares with Corman’s other roaring Poe adaptations: the ripe screenplay that channels Poe via Freud, Gothic landscapes painted in bright Technicolor strokes, hallucinogenic inner mindscapes, and Price’s delightfully camp performance. What Masque brings to the party that makes it so extra are delirious scenes of freakery, Satanic worship, Dionysian bacchanals, and even more hallucinogenic imagery. Nicolas Roeg’s cinematography captures the bizarre visuals perfectly. In all, Masque is a feverish combination of drive-in and avant-garde, the essential psychedelic horror film. Dialogue and audio snippets from the film have been sampled in songs by doom metal bands such as Electric Wizard, Theatre of Tragedy, and Bell Witch, which adds to the film’s cult pedigree.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (Tobe Hooper, 1974)

There’s a smorgasbord (please forgive the food reference) of reasons why this film is so effective. I never fail to be mesmerized by its uncanny oscillation between extreme poles. The grainy, 16 mm cinematography gives the film a documentary quality, which goes a long way toward selling the film’s claims of being based on actual events. However, other filmic elements give it an experimental, avant-garde quality, with these techniques most clearly on display during the climatic, Mad-Hatter-tea-party-from-hell dinner scene during which the viewer is barraged with rapid, disorienting editing, dissonant sound design, and extreme close-ups. Among the brutally bizarre elements of the film are moments of perverse beauty, epitomized by the shot of the young lovers running through country fields with a rotting, decrepit house looming behind them. The film’s abrupt transitions between horror and black humour are also particularly effective. One specific example of these transitions that immediately comes to mind is when Sally pulls a knife on the Cook, who disarms her with a swat of a broom. When I watch this film with an audience, the smack with the broom never fails to get a laugh – how dangerous can a broom really be? – but the laughs quickly die off as the Cook overpowers Sally, leaps onto her, and begins beating her with the broomstick, the cracks of the stick hitting her body expertly emphasized with Foley. After the Cook drags Sally back to the cannibal family’s home, the perverse humour re-emerges, as the Cook yells and swats at Leatherface and the Hitchhiker like a demented Jackie Gleason. The film’s atmosphere is relentless, oppressive, and unforgettable. And we haven’t even gotten into the film’s themes, the most compelling probably being its look into capitalism’s horrific exploitation of human life and labour. If you watch only one horror film in your life, make it this one.

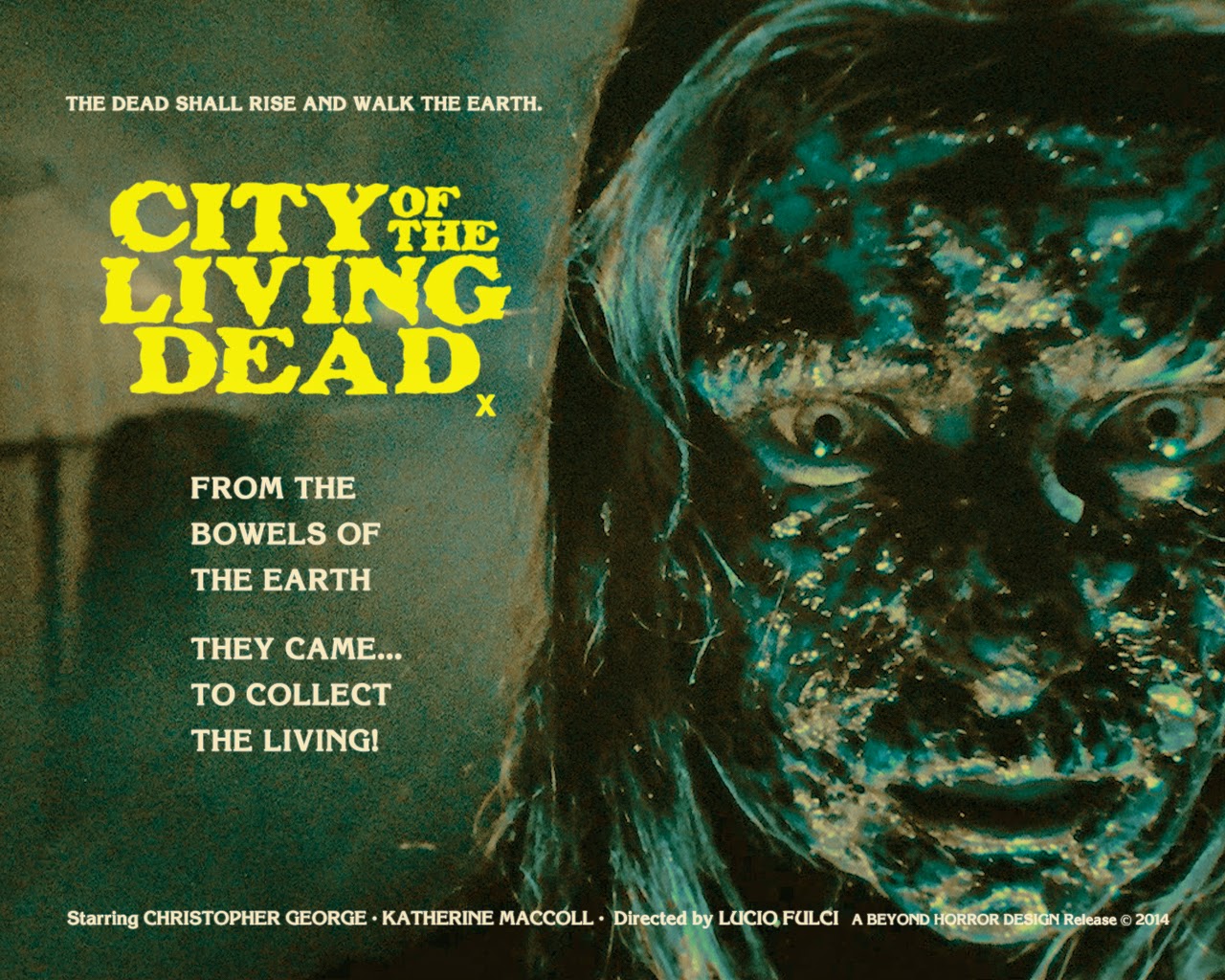

City of the Living Dead aka The Gates of Hell (Lucio Fulci, 1980)

Lucio Fulci boasts a filmography loaded with titles emblematic of the excesses of grindhouse-era Italian exploitation. Highly regarded among Fulci’s horror films are a loose trilogy of films depicting the various horror unleashed when portals to hell are ripped open. These three films are: City of the Living Dead (1980), The Beyond (1981), and House by the Cemetery (1981). Many consider The Beyond to be the best of these three films – some say that it’s Fulci’s masterpiece – but I’ve always preferred City, the first entry in the trilogy. With their eerie visuals, dizzying cinematography (Fulci’s unabashedly embraced the zoom lens), lack of logic, and disorienting sound design, Fulci’s horror films most closely resemble nightmares than any other horror films I’ve seen. This film stands out for me because it’s particularly ghoulish in its blatant blasphemy. A portal to hell is opened when a priest commits suicide, unleashing a swarm of zombies. One victim is murdered by an inverted baptism, as maggot-filled dirt is ground into her face. Another victim has a vision that causes a grotesque stigmata: her eyes bleed, and she vomits out her intestines. David Cook called Fulci’s horror films “delirious, dreamlike descents into hell,” and I don’t know if horror gets much more savagely sacrilegious than this.

Mark Bernard is Assistant Professor of English at Siena Heights University in Adrian, Michigan, USA. He is the author of Selling the Splat Pack: The DVD Revolution and the American Horror Film (Edinburgh UP, 2014) and co-author of Appetites and Anxieties: Food, Film, and the Politics of Representation (Wayne State UP, 2014). He is currently writing a monograph about John Carpenter’s Halloween for Routledge’s Cinema and Youth Cultures series.