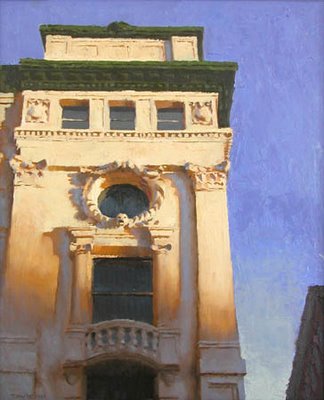

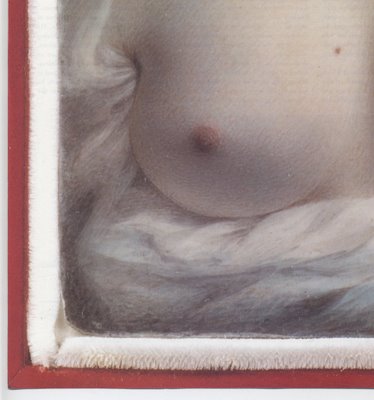

Awful drawing by Gary Panter reprinted by the Smithsonian Institution

Terrible drawing by Frank Stack also reprinted by the Smithsonian Institution

We are told for example that we can't judge the new "sophisticated and literate" brand of comic art without taking into consideration its words, or its politics, or its sadness, or some other redeeming external feature. Artists of the modern graphic novel, we are told, should not be measured by the standards applied to previous generations of artists (standards such as design, composition or linework). Instead, their pictures are to be read "like music notes on paper. They're just marks, unless you understand music, can read them, and then it becomes music... inside your brain."

My own view is that the emperor has no clothes. However, any critic taking such a position had better check in the mirror to make sure his own clothing is zipped up before venturing out in public.

Art is the great untidy thing, and I confess that I too am fond of artists with weak artistic ability just because I like their storytelling, or their style, or their spirit, or-- sometimes-- their weirdness.

One artist I like is Wally Wood, who worked for MAD Magazine and countless other publications.

Wood was no great draftsman. His figures were stiff and often formulaic. He did a lot of sloppy work. He never quite seemed to master perspective or foreshortening. (Note this cool spaceman with his head growing out of his shoulder:)

Despite his flaws, and his abundance of mediocre work, I really enjoy Wood's art. He was a seminal figure in popular culture, someone who made important contributions to the imagery of science fiction and satire. His subversive imagination worked well with Harvey Kurtzman's to challenge the "creeping meatballism" of 1950s and 1960s culture.

Note the beatnik in the background of one of Wood's trademark weird illustrations from MAD:

Another frequently mediocre artist I like is Will Eisner, the creator of The Spirit and the founding father of the graphic novel. Eisner's meager drawing ability was barely adequate to convey his talent. He had no great aptitude for design or composition, but he was a creative story teller with a strong visual sense. He wisely turned to a series of ghost artists (including Wally Wood) to help him.

Eisner's art was just competent enough to portray the cinematic angle shots and shadows for which he was justly famous.

Eisner's Spirit was smart, funny and a joy to read.

There are other artists whose style, personality, wit or story line compensate for their artistic weaknesses. Some that come readily to mind are Lynda Barry, Harvey Kurtzman, Scott Adams and Garret Gaston.

Is it fair for me to criticize some current artists (such as Chris Ware, Art Spiegelman, Gary Panter and Frank Stack) for their mediocre drawing while forgiving other artists (such as Wood and Eisner) for their own lack of talent? What's the difference between the art I like and the art I don't?

First, I find it is much easier to accept mediocre art when it is unpretentious. Artists such as Wood and Eisner toiled for decades pouring creativity onto cheap pulp paper. They were under appreciated and underpaid. By contrast, their modern counterparts found early fame and are lauded in deluxe coffee table books from the Smithsonian Institution filled with gushing self-congratulatory prose about how the new generation has elevated the medium:

When Raw finally came to an end and Spiegelman collected his pulitzer prize for Maus, few would deny that, in the right hands, the once lowly comic book rivaled film and the novel as a medium for sophisticated and literate narrative expression. On New York's Upper West Side, comics were now "hip" after all.As far as I'm concerned, unwarranted arrogance strips mediocre art of its charm.

Second, I am not impressed with the "hip" sophistication that supposedly redeems the current art. I am told that the new generation of graphic novelists deals with more mature and adult themes like the bleakness of modern life. To me, this is like saying that Wally Wood's art was more "adult" during the phase when he drew softcore porn for a living. Wood's "mature" subject did not redeem his art. Quite the contrary, Wood's pornography, like Chris Ware's adolescent nihilism, is actually less mature than MAD magazine. Tragedy is a fitting subject for adult art but mewling, bleating, puking and whining do not redeem mediocrity in art, they underscore it.

Wood was a pioneer in an infant medium. He fought battles for artistic freedom and artists rights that his successors never had to fight. Despite his prolific output, he was never compensated as well as his successors have been. He was not unaware of bleakness in life; he had health problems and struggled with the bottle and depression before he killed himself. But Wood was never narcissistic enough to fill graphic novels with his personal demons.

Wood's generation felt obligated to try to get things right artistically, and Wood fell short of the highest standards of draftsmanship. However, he left a great legacy, a generation of wonderful images and stories of children, rocketships, and alien creatures. He had a great influence. A mediocre artist could do a lot worse.