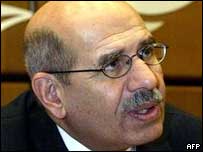

Mohamed ElBaradei has worked for more than 20 years at the IAEA

|

United Nations nuclear watchdog chief Mohamed ElBaradei and his agency were awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2005.

His post has often put him in the spotlight.

Mr ElBaradei is a former Egyptian diplomat who joined the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 1984 and held a series of high-level policy positions in the organisation before becoming director 13 years later.

He secured a third term at the helm of the agency after the US eventually agreed to back him, although relations between Washington and the IAEA have not been without tensions in recent years.

For although Mr ElBaradei has agreed with the current administration on a number of key nuclear-related issues, he is not afraid to speak his mind.

He has particularly lambasted what he sees as double standards on the part of countries which have nuclear weapons, but which seek to prevent others from procuring them.

"We must abandon the unworkable notion that it is morally reprehensible for some countries to pursue weapons of mass destruction, yet morally acceptable for others to rely on them for security - and indeed to continue to refine their capacities and postulate plans for their use," he has declared.

Treading carefully

Born in Egypt in 1942, Mr ElBaradei studied law at the University of Cairo. He began his career in the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1964, and worked in Egypt's permanent mission to the UN both in New York and in Geneva.

Mr ElBaradei holds a doctorate in international law from New York University's law school. In 1980 he became a senior fellow in charge of the International Law Programme at the UN's Institute for Training and Research.

|

The Iraq experience demonstrated that inspections can be effective even when the country being inspected is less than co-operative

The Iraq experience demonstrated that inspections can be effective even when the country being inspected is less than co-operative

|

His early diplomatic training is apparent in everything he does - from the relaxed but careful way he talks to journalists, to his dealings with countries' nuclear programmes.

Since taking over from Swedish diplomat Hans Blix in 1997, Mr ElBaradei has employed diplomacy to deal with nuclear rows over Iraq, North Korea and Iran, and insists that even in the most difficult situations, progress can be made.

"Verification and diplomacy, used together, can work," he says.

"The Iraq experience demonstrated that inspections can be effective even when the country being inspected is less than co-operative. All the evidence indicates that Iraq's nuclear weapons programme had been effectively dismantled in the 1990s through IAEA inspection, as we were nearly ready to conclude before the war. Inspections in Iran over the past year have also been key to uncovering a nuclear programme that had remained hidden since the 1980s."

Tensions with US

Mr ElBaradei's views on Iraq did not always accord with the Bush administration, and his approach to Iran has raised tensions with the US and its allies in the European Union.

They want a tougher response to the country's uranium enrichment activities - a part of the nuclear fuel cycle that can be directed to both energy and weapons purposes.

However, Mr ElBaradei has found consensus with President Bush on a number of issues - notably on the need to supplement the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, the main treaty that seeks to limit the spread of nuclear weapons, and the need to penalise states that opt out of the treaty after acquiring nuclear equipment under the guise of a peaceful programme.

Both are keen to find a way to deny countries that refuse to sign the treaty, or those that are suspected of cheating on it, access to technology that enriches uranium or reprocesses fuel that has been used in peaceful nuclear reactors and which can also be used in nuclear bombs.

~RS~q~RS~~RS~z~RS~03~RS~)