August 21, 2010, 2:54 am

Things are looking bleak for the economy; Goldman Sachs (no link) is predicting that 2nd quarter GDP growth will be revised down to 1.1%, and it’s downhill from here.

Yet from late 2009 until just the other day, all the Very Serious People were mainly concerned about the possibility of surging interest rates. Why?

I was looking back at some of my own notes about what happened last fall. At the time, there was serious consideration among the Obama people of pushing for some kind of second stimulus; what its chances might have been is hard to say. But the point is that they backed off. Why? My understanding is that they bought into the big scare of the time, which was that there was a “carry trade bubble” in the bond market, and terrible things would happen when it burst.

No, this never made sense. Anyone who looked at recent Japanese history should have realized that with a depressed economy, low rates could and did last a very long time.

And some of the scenarios being proposed were just plain bizarre: the bond bubble will burst, and this will plunge us into recession, and the Fed will have to buy up government debt, and this will mean inflation too. Really.

And then the whole story shifted: suddenly it wasn’t the carry trade, it was sovereign debt risks, we’re all Greece.

And now there’s a new one: you see, low interest rates will cause deflation. Really (near the end).

And though the story shifts, the moral is always the same: the little people have to suffer.

August 20, 2010, 10:57 am

So policy makers live in awe of savage priests, who demand that we sacrifice virgins to the invisible gods of the bond market. But what puzzles me is this: why do the priests have such influence? Never mind the victims (we never do); anyone who listened to the priests has lost a lot of money.

A case in point:

Morgan Stanley, the most bearish among the 18 primary dealers that trade government securities with the Federal Reserve, acknowledged that its forecast that Treasury yields would rise this year was misguided.

…

Morgan Stanley had forecast that a strengthening U.S. economy would lead to private credit demand, higher stock prices and diminish the refuge appeal of Treasuries, pushing yields higher. David Greenlaw, chief fixed-income economist at Morgan Stanley, said in December that yields on benchmark 10-year notes would climb about 40 percent to 5.5 percent, the biggest annual increase since 1999. The firm reduced its forecast to 4.5 percent in May and to 3.5 percent last week.

The 10-year note yield fell as much as 4 basis points to 2.53 percent today, the lowest level since March 2009. Yields have declined 10 basis points in the last five days and about 46 basis points in four weeks.

I wrote about this forecast in November 2009, because I believed that such predictions were having a big impact on the Obama administration. And I tried to point out then that the same people confidently declaring that there was a bubble in the bond market completely missed the housing bubble.

And yet these people continue to influence policy.

August 20, 2010, 2:33 am

In today’s column I write about the way fear of invisible bond vigilantes is driving demands for austerity. I didn’t have space to deal with the other part of the austerity cult: the belief that the gods will reward austerity with economic expansion. But it’s equally unfounded in any actual evidence.

In a terrific new working paper, MIke Konczal and Arjun Jayadev look under the hood of an Alesina/Ardagna paper that is being widely cited as evidence that austerity will lead to growth. They look to see how many of the austerity -> growth episodes actually involve fiscal contraction in a slump. Here’s a comprehensive list of those cases:

Ireland 1987

And as I among others have noted, the things that drove Irish expansion — devaluation, a boom in its largest trading partner, and a sharp fall in interest rates — have no relevance to the United States today.

All of which goes to remind us with how little wisdom the world is governed.

August 18, 2010, 12:49 pm

Not likely to attend the conference

Not likely to attend the conferenceI’m off to Sweden, where I’ll be hanging out with tattooed Goth hackers regional scientists. I don’t know how much posting, if any, I’ll be doing.

August 18, 2010, 12:40 pm

There was a moment last fall when the Obama administration could have pushed for significantly more aid to the economy, with a reasonable chance of getting something through. But the administration balked — largely, I believe, because it believed warnings that the invisible bond vigilantes were about to strike. And there was a lot of talk at the time about Japan, which was supposedly losing the confidence of investors. As usual, pure speculation was reported as fact:

For jittery investors, Japan’s rising sea of debt is the stuff of nightmares: the possibility of an eventual sovereign debt crisis, where the country would be unable to pay some holders of its bonds, or a destabilizing collapse in the value of the yen.

The only evidence given was a bump up in 10-year bond rates, to a horrifying, um, 1.4 percent. Here’s what has actually happened to those yields since:

Bloomberg

Bloomberg Yes, Japanese long-term debt is now yielding less than 1 percent. Oh, and the CDS spread is more or less comparable to other non-Italy G7 countries.

We’re facing a slow-motion catastrophe because policy makers were afraid of the wrong things.

August 18, 2010, 12:30 pm

We’ve been scooped! Yesterday Robin and I were talking about the implications of a balance-sheet view of the economy’s troubles, and realized that it makes a strong case for using Fannie and Freddie to bring down homeowners’ debt burdens.

And meanwhile, Bill Gross was laying out a proposal.

You can quibble with the details, but Gross is right:

“The American economy is approaching a cul-de-sac of stimulus — both monetarily and fiscally,” Gross told the crowd at the Treasury Department, “which will slow to a snail’s pace, incapable of providing sufficient job growth going forward.

“Unemployment rates will approach and remain at double digits unless positive fiscal stimulus is provided in the next six months.”

The important thing is to act — even if it’s not the perfect answer.

August 18, 2010, 9:18 am

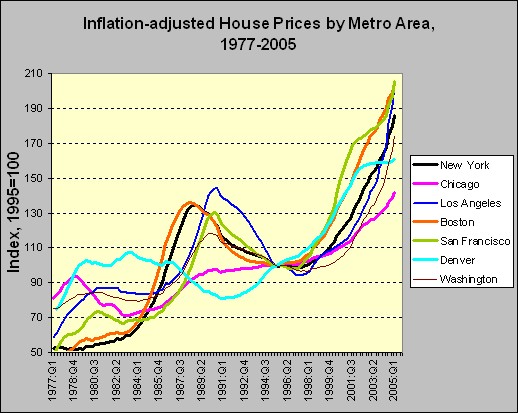

Yves Smith says most of what needs to be said about the Boston Fed study saying that nobody could have called the housing bubble. I’d just add that it’s helpful to look at what we knew back when. Here’s a picture from Kash of house prices up to early 2005; by the way, these were OFHEO prices, which most now believe understated the rise, which was better shown by Case-Shiller. But here’s what it looked like, even then:

Given this kind of picture — and given the fact that the late-80s rise in southern California was, in fact, a bubble — how could you not be very worried? And when you looked at the rationalizations for high housing prices being given at the time, it was obvious that they were questionable.

Sorry: the evidence just screamed bubble. No excuses for those who didn’t want to hear it.

August 17, 2010, 11:33 am

I get a lot of comments along the lines of “Would you please respond to the criticism of your work in ______?”

Um, no. Do you have any idea how many articles there are out there attacking me? I literally don’t have the time to respond to them all, or even to differentiate between the usual sliming and actually interesting critiques.

Just saying.

August 17, 2010, 11:14 am

A brief revisiting of the issues I raised more than a year ago regarding alternative views of interest rates.

This was never a question of simply forecasting what was going to happen to rates. It was about what would drive rates.

The view of Ferguson and others, back then, was that government deficits would drive up interest rates, choking off recovery. I and others argued that this was bad macroeconomics: interest rates would rise if and only if recovery took place. More specifically, short-term rates would stay near zero as long as the economy was deeply depressed; long-term rates would depend on expectations about the future of short rates, and hence on prospects for recovery.

So the key point is not the fact that rates are now considerably lower than they were when that debate took place; it’s the fact that rates have fluctuated very much with optimism about recovery, never mind the deficits.

In fact, if you had a naive loanable funds view, you’d expect the recent downgrading of expectations to drive rates up, not down — after all, a weaker economy means bigger deficits. But the opposite has, in fact, been happening.

The bottom line is that events have utterly confirmed one view, utterly rejected the other. Too bad such things don’t count in politics.

August 17, 2010, 11:04 am

I’ve just finished rereading Richard Koo’s The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics, as part of a multi-book review project. It’s one of the few books out there that talks about what you should do in the aftermath of a burst bubble — almost everyone else obsesses on the causes of the bubble, and possibly on how to prevent the next bubble, neither of which is the clear and present issue.

There’s a lot to like in Koo’s idea of balance-sheet recessions — how an overhang of corporate debt held down Japan’s economy, how an overhang of household debt is doing the same to America. And Koo is unique — which is a good thing — in arguing both that protracted deficits are sometimes desirable, and that Japan is actually a success story in the sense that its deficits made it possible to repair corporate balance sheets without a Great-Depression-level slump.

I do have a beef with his book, however. Koo makes a good case for the important of balance sheets, and the usefulness of fiscal policy. But he goes on the warpath, not just against the idea that monetary policy can do it all, but against the idea that it can do any good whatsoever. And I think that’s wrong.

Read more…

August 16, 2010, 8:33 pm

P. O’Neill — not the former Treasury Secretary — has a great blog post about Ireland, its banks, and its mess. Strangely comforting for an American; we’re not alone, it turns out, in our policy morass.

August 16, 2010, 4:02 pm

I agree with everything this NYT editorial has to say about the economics of widening international imbalances. Where I disagree is on the issue of negotiating strategy. My colleagues believe that we should lecture the Chinese on what a bad thing they’re doing, but not actually threaten sanctions, lest we start a trade war. My belief is that this gets us nowhere.

Right now, China is following a policy that is, in effect, one of imposing high tariffs and providing large export subsidies — because that’s what an undervalued currency does. That should be a violation of trade rules; it might in fact be a violation, but the language of the law is vague on the subject. But leave aside the fine print of the law for a moment: what China is doing amounts to a seriously predatory trade policy, the kind of thing that is supposed to be prevented by the threat of sanctions.

Yet the Chinese have taken our measure, and decided that we won’t act. Until or unless that changes, we’re just whistling in the wind.

I say confront the issue head on — and if it leads to trade conflict, bear in mind that in a depressed world economy, surplus countries have a lot to lose from such a conflict, while deficit countries may well end up gaining. Or to put it differently, right now we’re in a world in which mercantilism works. In the long run we’ll emerge from this kind of world; but in the long run …

August 16, 2010, 3:19 pm

My trip yesterday was actually to Niagara Falls, to talk to the Canadian Bar Association. In preparation, I did some homework; and to be honest, I came away a little less sanguine about Canada than I started.

Everything I and others have said about the Canadian banking system and its virtues is true. But in other respects, there do seem to be some worrying signs.

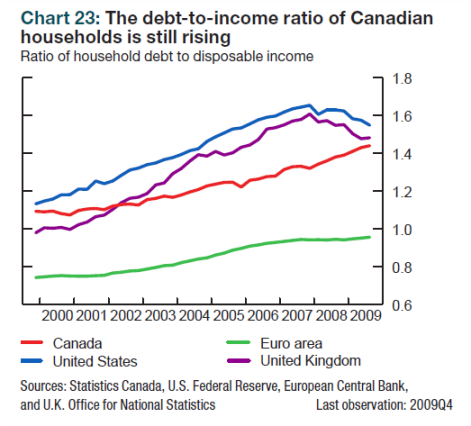

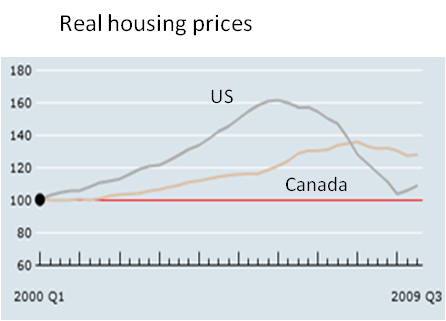

First of all, Canadians borrow and spend like, well, Americans:

Bank of Canada

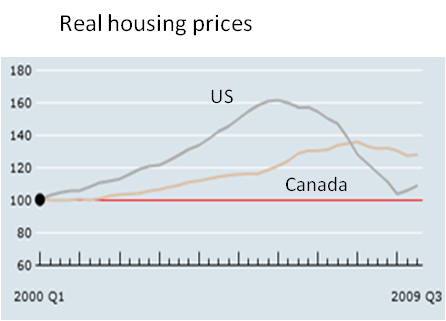

Bank of Canada And while they managed to avoid getting caught up in the big, synchronized North Atlantic housing bubble, trends since are not completely reassuring:

The Economist

The Economist I’m not making any predictions here, just noting that if we go beyond banking to ask about household balance sheets and risks thereto, things up north bear watching.

August 16, 2010, 10:45 am

I was sorely tempted to break the NYT rules on obscenity when I fired up my notebook this morning and saw the 10-year bond yield: 2.59 percent. We’re now almost back to the Oh-God-we’re-all-gonna-die yields at the height of the financial crisis.

Those invisible bond vigilantes are really cunning, is all I can say.