A slightly different version of this article was first published at Your Wardrobe Unlock’d.

(Click any illustration to view the full-sized image.)

The Victorian lady has a dress for every occasion. This idea isn’t foreign to modern women. After all, you might wear jeans and a t-shirt on the weekends, then switch to a skirt and blouse for the office, and at the end of the day, slip into a little black dress for dinner.

Some 19th century dresses can be worn for more than one purpose, but very specific rules govern when each type of gown is appropriate. “It is in as bad taste to receive your morning calls in an elaborate evening dress as it would be to attend a ball in your morning wrapper.”—The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, pg 23 (1872)

Garments are classified by the time of day they’re meant to be worn: morning, afternoon, or evening. Beyond that, they have a multitude of sub-categories. Accessories must be carefully chosen according to the hour and occasion. After all, “. . . in an in-door dress, heavy walking-boots would be as inappropriate as a bonnet or parasol.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 38 (1870)

How can you possibly keep track of the differences between so many garments? Unfortunately, such details were often kept secret (perhaps to maintain a gap between the social classes), so modern costumers have only a vague idea of the rules for Victorian dressing. Nonetheless, much can be pieced together by examining period fashion magazines and etiquette manuals. Let’s see what we can deduce.

Daytime

Visitors are not expected until the late morning. Therefore, a woman can begin the day in a looser, more comfortable gown. However, “A lady should never receive her morning callers in a wrapper, unless they call at an unusually early hour, or some unexpected demand upon her time makes it impossible to change her dress after breakfast.”—The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, pg 28 (1872)

When you dress to receive visitors, you are expected to wear something nice, with a high neckline, long sleeves, very little jewelry, and “. . . there should be no cap or head dress worn.”—The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, pg 28 (1872)

As for shoes, “Slippers of embroidered cloth are prettiest with a wrapper, and in summer black morocco is the most suitable for the house in the morning.”—The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, pgs 27, 28 (1872)

During the afternoon, you might choose to go out visiting, attend to errands, or stay at home and receive visitors. If you have many friends, it’s recommended that you set a particular day during which visitors are welcome. The “at-home” day is printed upon your personal card and passed out to your friends and acquaintances. Doing this allows you to dress appropriately on the afternoons you’re expecting visitors.

Necklines can be somewhat lower in the afternoon, with a round or high V-shape that doesn’t expose the bosom. Sleeves can be shortened to elbow-length. Lace might be worn at the throat, but jewels are frowned upon. Gloves must be worn outdoors, along with a bonnet or hat.

No matter what you wear, make certain you dress completely before going outside. “It is a mark of ill-breeding to draw your gloves on in the street. . . . Take a few moments more in your dressing-room and so arrange your dress that you will not need to think of it again whilst you are out.”—The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, pgs. 110, 111 (1872)

Interestingly, some dresses can be worn for more than one occasion. Therefore, a visiting toilette might double as a reception gown or a walking dress, depending on how it’s cut.

During the day, you might wear one of the following types of dresses:

|

|

|

Sacque

The Victorian equivalent of a bathrobe, the sacque should be worn only in the privacy of the bedroom, perhaps while breakfasting in bed or doing your morning toilette. A ribbon corset may be worn underneath.

Related to the sacque is the combing jacket. This is a short, lightweight cape or loose robe that’s worn over your nightgown or morning dress to prevent shed hairs from falling on your clothing while you style your hair.

Wrapper

A plain, comfortable gown, the wrapper is worn while doing household chores in the morning or while breakfasting. Though not intended for wearing outdoors, the wrapper is nonetheless modest enough that it can be worn if visitors drop by unexpectedly. It goes without saying that a corset must be worn under a wrapper. A large apron can be tied over the wrapper and removed in the event of visitors.

Many wrappers button down the front, or are cut loose with a sash to give them shape—which makes them ideal for pregnant women and nursing mothers.

House Dress

More elaborate than a wrapper, an at-home dress is worn to receive guests in the late morning or early afternoon. Up until the 1870s, this might be an open wrapper worn over an embroidered petticoat or white skirt, or it might be a simply trimmed gown in its own right. Later on, the tea gown served a similar purpose.

The house dress may be trained or not, and is often worn with a small lace cap. However, “It is much better to let the hair be perfectly smooth, requiring no cap, which is often worn to conceal the lazy, slovenly arrangement of the hair.”—The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, pg 27 (1872)

Visiting Toilette

Typically an afternoon dress, a visiting ensemble is worn while paying calls on friends and neighbors. If desired, it can have a slightly lower neckline and shorter (elbow-length) sleeves. Embellishments should be limited, and the bodice is often styled as a jacket.

Gloves and a bonnet—never a hat—are worn with a visiting dress. “A lady paying a visit may remove . . . neither her shawl nor bonnet,” because this would imply that she intended to stay longer than was considered polite.—Mrs. Beeton’s Book of Household Management (1861)

Promenade Dress

This gown is intended for a morning walk or carriage ride. As it’s meant to be seen, it’s often elaborately decorated. It may be trained or walking length, depending on whether you desire to promenade by foot or by carriage. “Rich and strong colors” are recommended, but not vivid hues.—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 44 (1870)

Carriage Toilette

This type of dress can be worn while visiting, or during a carriage ride around town. (Harper’s Bazar, pg 461 (July 17, 1869)) It’s often trained and heavily embellished.

Walking or Street Dress

This gown should be hemmed several inches shorter for ease of walking outdoors. It may be simply or elaborately decorated. Such a dress should “. . . be of quiet colors, and never conspicuous. Browns, modes, and neutral tints, with black and white, make the prettiest dresses for the street.”—The Ladies’ Book of Etiquette and Manual of Politeness, pg 29 (1872)

Trained walking dresses are common, but frowned upon, as they tend to gather up debris from the street. Boots or low-heeled shoes should be worn, along with the usual out-of-door accessories, such as gloves, a hat or bonnet, and a parasol.

Traveling Ensemble

Whether traveling by train, coach, or ship, this outfit must be entirely practical. Fabrics should be sturdy and dark-colored to conceal dust, soot, and mud. Shades of navy, brown, and dark green are popular choices. Hem your skirts relatively short and keep embellishments to a minimum. Sturdy boots should be worn, along with cloth or thread gloves—not kid. You may wear a hat or bonnet, but feathers and flowers should be left off. A cloak, duster, or heavy shawl is desirable, as well.

If in deep mourning, keep in mind that a veil of dark brown or green is better suited to traveling, “. . . since no dress is so disfigured by the dust of travel as close black.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 93 (1870)

Country Toilette

Tending towards simplistic, practical styles, these dresses are made to be worn while visiting the country. You will find them of less-expensive fabrics, particularly in plaids and floral prints.

Seaside Costume

This style of dress is worn while visiting the beach, or perhaps while yachting. Thus, it should be of fabrics that will not be ruined by damp breezes or saltwater mists. Seaside toilettes often incorporate a nautical theme, having sailor’s collars and military-inspired embellishments. Blue, red, and white are popular colors, especially in stripes. For practical reasons these dresses should be of walking length and not trained. Hats should be of cloth, for, “Straw soon becomes limp in sea air. . . .”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 91 (1870)

Watering-Place Costume

This dress is intended to be worn “in country-houses, at watering-places, or for out-of-door fetes, lawn parties, and other summer festivals.”—Harper’s Bazar, pg 408 (June 28, 1873)

Judging by fashion plates, watering-place costumes are made of lightweight fabrics, but elaborately trimmed, sometimes with a short train. They may, on occasion, be made with an evening neckline and sleeves.

Toilette for Church

While many attend church to be seen by others, keep in mind the solemnity of the occasion. Gowns should be of good taste, not ostentatious. Strive for a simple, modest elegance. Above all, avoid fabrics that rustle or make noise. “Rustling silks are especially annoying in church, as the least movement of the wearer causes them to make a noise sufficient to make inaudible for a moment the voice of the preacher.”—The Art of Dressing Well, pg 55 (1870)

Reception Dress

The reception dress is the most formal of daytime gowns, and as such, is quite versatile. It can be worn to church, or to a daytime social event, such as a reception introducing a guest. It can also substitute for a visiting toilette, or be worn for dinner. These dresses are styled for the afternoon, with elbow-length sleeves and a modest square or V-neckline, but made of fancier fabrics.

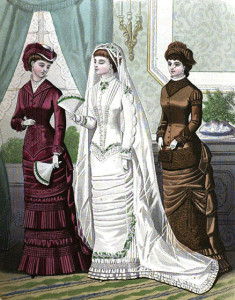

Wedding Gown

Though the subject of every woman’s dreams, the wedding gown doesn’t need to be elaborate. White is, of course, the most fashionable color, at least after Queen Victoria’s wedding in 1840. However, economical brides will marry in their best dress, whatever color it happens to be, so they might wear it again. For a daytime wedding, the neck should be high and the sleeves long.

In the second half of this article, we’ll look at the rules for evening and sportswear.

These pages are very interesting, and much needed by the French Fashion doll collector. Thank you for Part I and Part II.

Fabulous information. Thank you.

Drawing a comic set in the Victorian era. This site has been extremely helpful in clothing the lady of the house properly. Thank you!

Pingback: How to host a Victorian picnic - Recollections Blog

Thanks so much for this! For an exhibition catalogue essay I’m writing I’m trying to find a reputable source to cite, stating that respectable women in London/Paris/NYC/Boston during the 1880s and 1890s would never allow their ankles to show, in public…assuming that this was actually the case. Can you please help?

MANY THANKS, and best wishes,.

Nancy G. Heller

Certainly! The “no ankles” thing is a myth. Everyday dresses would generally touch the top of the foot, but walking dresses and sporting dresses (hunting, cycling, skating, tennis, etc.) were much shorter. There are illustrations from the 1880s that show hunting skirts ending just below the knee. Bathing suits were also short enough that ankles showed. If you search on Pinterest, you’ll find lots of examples. Hope this helps!

Were certain colours not allowed in Church or could any colour be considered appropriate? I know my Grandmother would probably faint if I wore bright red to mass but I am unsure if this is a historical rule or simply her own idiosyncrasy.

My second question would be regarding what would be worn in areas like beach towns or even venice where water is more likely to be part of the daily walk. Would something more similar to a watering-palace costume or sea-side costume be worn more regularly on a day to day basis?

Thank You so much for these resources, your hard work is a gift!

Good questions! I haven’t read anything that said certain colors were forbidden at church. My instinct says somber colors were probably more encouraged, but I don’t have any evidence to back that up, and my assumption could just be based on decades of Hollywood falsehoods. It’s entirely possible that seaside or watering-place dresses were worn more often by residents on the coast, or maybe they just modified regular dresses to be more suitable for the climate (lighter fabrics for the heat, for example). I don’t have any definite information on that, but it’s an interesting question to ask! I’m sorry I don’t know the answer.

very nice! I really needed this for a comic I am making with my friends, thank you!!

This was very interesting! I’m writing a book about a victorian debutante and i would just like to ask a quick question. Would a watering-place costume be worn to a garden party?

Harper’s Bazaar specifically includes “lawn parties” as acceptable for watering-place costumes, so I would assume a garden party qualifies. I think the daytime rules would apply, if it’s an afternoon party: elbow length or full-length sleeves, a moderate neckline, nothing too revealing, but not as buttoned-up as a morning dress would be. If it’s summertime, thin, lightweight fabrics would be used, like gauze, muslin, voile, lawn, etc. Hope this helps!

Yes, thank you! I’ve got another question. If, after a dinner party, several events were to take place (in my case it would be a concert, two soirées and a ball), could a ballgown of been worn?

I enjoyed reading this. Besides, it taught me a bit about my Victorian dress I recently purchased. I bought along with that the Babyonline Petticoats for Women Floor Length 6 Hoop Skirt Crinoline Slips Long Underskirt for Quinceanera Dresses

.I had to watch videos on how to fold it, how to set down with it on, and how to get in the car with it on. This article helped a lot. Thank you.

Have you ever considered breaking the rules and designing your own authentic Victorian costume that goes against traditional norms? How can you push the boundaries while still staying true to the essence of Victorian fashion?

Great question! Given that an “authentic Victorian costume” is historical in nature, it’s extremely difficult to go against the traditional norms without losing that which makes it authentically Victorian. I’ve seen a few exceptions, such as a late bustle dress made in the style of a Starfleet uniform (TNG). It’s not authentic in the sense that you might find one in a Victorian fashion magazine, but it was cleverly done and followed the historical model as closely as possible, while still being obviously Star Trek. This is quite hard to do, so there aren’t many costumes like this. Steampunk is another genre that can be done in a historical fashion, but with its own twist. Still, I’m not sure you could claim it’s authentic once the steampunk changes are made. It all depends on how authentic you want to be and how far you’re willing to bend the rules.