Cheers! Lonely Otakus: Bilibili, the Barrage Subtitles System and Fandom as Performance

/My book, Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture, was released earlier this year in a translation intended for the Chinese market. My translator, Xiqing Zheng, also recently completed a dissertation, Borderless Fandom and The Contemporary Popular Cultural Scene in Chinese Cyberspace. Given my ongoing interest in transnational studies of fan culture, I asked if I might publish a small excerpt from that dissertation here -- in this case, dealing with a form of fan participation that has been taking many parts of East Asia by storm in recent years.

Cheers! Lonely Otakus: Bilbili, the Barrage Subtitles System and Fandom as Performance

by Xiqing Zheng

Barrage subtitle system is started by the Japanese website Niconico douga ニコニコ動画 —a site for otaku community, the ninth most visited website in Japan in the year 2016. The comments on a barrage subtitle streaming website, instead of appearing under the video in a special “comment” section, appear directly on the video screen. Synced with the video, the comments would appear at certain playback time when the video is played. The default setting makes the comments displayed in black font and white color, flying over the video from the right to the left at a random height; but fonts and special effects can be specified in advanced settings.

The phrase “barrage” is popularized by several anime directed by Yoshiyuki Tomino富野由悠季, including Mobile Suit Z Gundam (機動戦士Ζガンダム Kidō Senshi Z Gandamu 1985-1986) and Aura Battler Dunbine (聖戦士ダンバイン Seisenshi Danbain, 1983-1984), in which a line “The barrage on the port side is too thin! What should we do?” grew viral in the otaku community. Besides, Toho project, a phenomenally popular shooter game since the late 1990s allows bullets to form complicated patterns—a barrage so complicated that it later becomes a spectacle in the gaming community (see Lin and Gao for more information). With such background, netizens on Niconico chose this word to describe heavily commented scenes on a Niconico video as “barrage,” that resembles a scene with flying bullets across the screen in video games. Later this name is given to all the comments on the screen.

Chinese otaku established several video sharing sites, directly imitating Niconico; the most influential ones are AcFun and Bilibili. Here I will primarily use Bilibili as an example. Founded in the year 2009, it is now the most influential and popular barrage subtitle website in China. “Bilibili” is the nickname for a popular female character Misaka Mikoto御坂美琴 in the light novel and anime, A Certain Scientific Railgun (To Aru Kagaku no Reirugan とある科学の超電子砲, 2009-2010, 2013). Since it was originally designed to be majorly catering to the Japanese ACGN otaku, Bilibili has a specific section for all new Japanese animations. Besides, it provides sections for the DIY fans to showcase their talent in singing, dancing, music performance, painting, fan video editing, video game playing, etc., all in the realm of Japanese ACGN culture (acronym of “Anime, Comic, Game, Light Novel”). Because of Bilibili’s growing popularity, it now reserves sections for all types of popular culture, including, for example, American TV series, films, talk shows, Chinese TV dramas, variety shows—the contents incorporated into the website actually reflect the diverse interest and versatile talents of the otaku community.

After the success of Bilibili, the barrage subtitle system became known to the mainstream. Many Chinese online streaming websites, including the mainstream Tudou, Tencent, now support barrage subtitles, yet “Site A” and “Site B” remain the most important websites for the otaku community. According to an interview, Chen Rui the manager of Bilibili says, that he is not worried about the mainstream websites adopting the barrage subtitle feature at all, because what matters is not the configuration, but the content. The content does not only refers to those videos uploaded, but also the interactive barrage subtitles posted by the viewers. The chemistry of these otaku-oriented sites comes from the videos, the viewers, and most importantly, the interaction between the websites and the otaku users.

Otaku, as it is currently used in daily practice, refers to lovers and heavy consumers of Japanese manga, anime, games, and light novels. The word otaku is an honorarium word for “your house,” and thus “you,” was used by a group of Japanese sci-fi fans in the 1960s for addressing each other inside the community. The word gained wide public attention when a critic, Akio Nakamori, ridicules these heavy consumers of totally unrealistic and childish media products, with the word “otaku.” The otaku culture came to Chinese mainland together with the Japanese manga, anime and game, as early as in the 1980s. For a certain period of time, Japanese anime obtained a position close to mainstream children’s entertainment until in the mid-2000s, when the government shut down the legal broadcast of Japanese anime in children’s programs around the country. The boundary between the mainstream and the otaku culture is therefore blurry and flimsy in China, yet still tangible. Less mainstream ACGN products first came to China in the form of pirated copies of Chinese translations legally produced in Taiwan or Hong Kong. Then online fansubs and fan translators become the major cultural mediators, who translate almost everything in this area. Only recently that the Japanese anime are again screened legally in China, with online video streaming websites purchasing legal rights from the Japanese anime producers. It is not difficult to imagine that most Chinese young people are more or less familiar with the Japanese ACGN culture. Naturally, most of the earliest Chinese fandoms are built on Japanese ACGN culture, even the fandom structures and activities are imitated from Japan through Taiwan’s mediation. With such a heavy influence from Japan, the “popular culture” understood and accepted by young generations in China then automatically involves Japanese ACGN culture. Therefore, the community of ACGN fans in China is not as clearly defined as it is in English speaking countries, where Japanese media traditionally lies in a comparatively marginal and subcultural realm.

While Japanese ACGN culture had been influential, the title of otaku is not widely adopted until about a decade ago. Most early Chinese fan websites and forums are female oriented. Until around 2005, the internet is much friendlier to text than to other forms such as picture and videos. This could be an important reason that in China, male fan culture, which heavily relies on visual elements, becomes observable much later than the female fan culture, which is sustainable on texts. With the entry of the male fan culture, the otaku community gradually evolves into an interest-based community that loosely develops around a certain set of original media products (typically Japanese ACGN culture, but has certain deviation), a community that is inherently heterogeneous but also share a similar set of vocabulary, logic and virtual space for residing. Currently, the otaku community in the Chinese-speaking world relies on several central websites for information and interaction. Barrage subtitle websites are of the most important components of their lives. Gender matters in this community, as the dualism between otaku male and fujoshi female is always present in the daily conversation, but mostly, they coexist comfortably in the same space with their shared interest.

The barrage subtitle system is a perfect presentation and embodiment of otaku’s desire in community and companions. This system, if not intentionally disabled, does not only make communication possible when people watch videos, it makes communication obligatory. Once it is sacrilege to interrupt the flow of image and time on the film screen, now it is the urge to communicate over the image that draw the audience together at these websites. It is not exaggerating to claim, that barrage subtitle system creates a new mode of watching, as well as a new mentality and meaning of being audience. Activities on the barrage subtitle websites have constituted an affective social ritual, performance and interaction in a virtual space; the video watching experience is itself a performance that confirms the social identity of being an otaku. Far from being void, boring and nonsense, these performances build up an alternative community in the virtual space. Such communications are observable in every aspect of the internet culture, yet it is extremely important for online otaku culture because it is—at least in China—a youth subculture that still yearns for collectivity and identification. For a virtual community consisting of people with their own interests in front of their own small screens, the importance of instant communication in multiple voices can never be underestimated.

Ultimately, barrage subtitle websites deeply integrate users’ input for the final view of each video uploaded, much more than websites without such a system. Viewing experience then becomes literarily a process of inserting oneself into the streamed material and the audience community, rather than a silent voyeur in the darkness. In many ways, barrage subtitles convey comparatively little (if any) content that would add on to viewers’ knowledge. Explanation and “encyclopedia” subtitles and translation subtitles also exist, but very limited compared to the tons of seemingly meaningless and senseless subtitles. As Hamano Satoshi observes, many barrage subtitles on Niconico come not from reason, but direct affect. Since the configuration of barrage subtitle system ensures a direct link between the comment and the commented, commentators need not elaborate their feelings into a long sentence, but only need to type out their immediate reactions and feelings. Hamano suggests that such comments represent a fragmented, or in his words, modular mode of consumption (5). I suggest, however, that the fragmented comments towards the specific details inside the videos visualize immediate reactions and close reading, inherent in fans’ viewing actions, but usually hidden when viewers are supposed to give generalized impressions and evaluations of a video. In other words, the consumption process does not become fragmented because the barrage subtitle system, it is fully articulated and presented in a directly visible way, something repressed in a traditional video streaming websites as YouTube. The fully presented consumption process therefore easily take the reading strategies and community conventions, constructing a space of discussion for close reading details that the otaku community relies upon in reaching consensus for further elaboration. In many ways, once the hidden and repressed process of close reading visualizes, it could be the most representative narrative that generates pleasure and intensifies allegiance.

With the development of the new media, especially the internet, we as the audience are encountering screens with videos on a daily basis. Theatrical experience these days becomes somewhat a nostalgic ritual for cinephilia, or a bait of spectacle, designed specifically the high-grossing, visual and audio effect laden blockbusters. While barrage subtitle websites, just as other types of online video-streaming websites, belong to the multiple screen culture in the contemporary daily life experience, barrage subtitle system revokes the collective aspect of theatrical film viewing in an unexpected way. The word “pseudo-synchronicity” accurately grabs the artificial sensation that all the audience for the same video are able to see the comments made by other viewers as if all these people are viewing the same material together. The experience on barrage subtitle websites challenges the iconic image of a contemporary viewer sitting lonely in front of a computer screen. However, the watching experience on barrage subtitle websites is still drastically different from the experience of watching films in an old fashioned movie theater, because the general silence and awing respect for the material on the screen totally disappears. The shared experience of watching, and especially the sharing synchronicity is expressed not through the shared silence and more permissible reactions such as laughing, but rather through actions that deem very impolite in a film theatre experience: speaking (or typing), which means uttering something significant to one’s point of view at the specific moment of the media material. The sense of shared interest and community comes from uttering comments that would trigger other people’s reaction or add on to someone else’s reaction. The viewing experience on barrage subtitle website is intrinsically multitasking, because with the barrage subtitle flying over the video, one not only response to the video itself but also the comments made by other viewers. The amount of reading required on a barrage subtitle website is almost a blasphemy for the streaming content, especially for the heavily commented videos.

When I talk about the conversational experience in barrage subtitles, however, it does not mean that the comments necessarily correspond to one another logically. Sometimes the content of comments is insignificant compared to its visual existence. What matters is that there are people who also watched the video and feel also the urge to express themselves at a particular point in time. When it comes to exciting moments, or significant moments, viewers would collectively post comments, stylized or randomly, to enhance the emotional intensity of the particular moment, be it humorous, sadness, or passionate. I will raise two examples below.

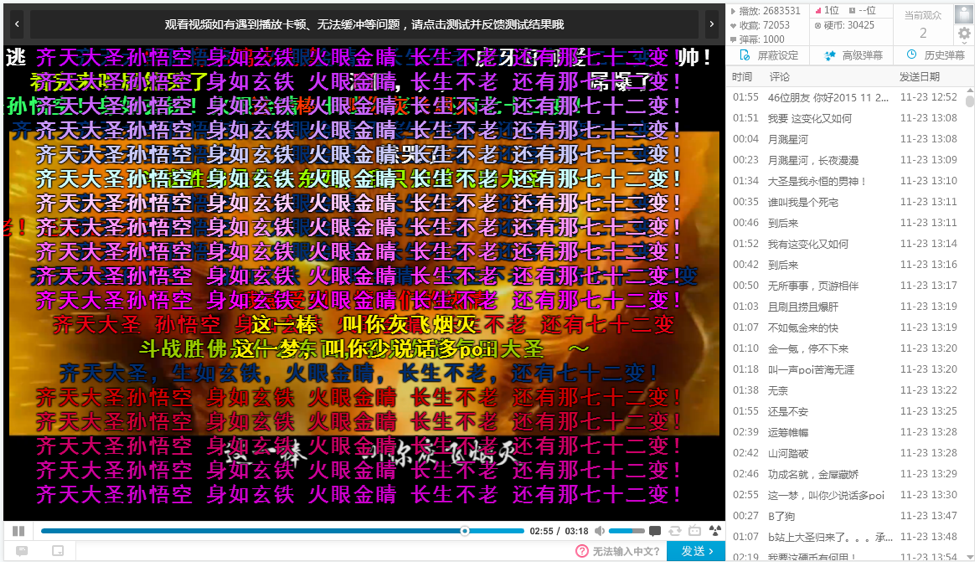

A fan remixed video of the domestic Chinese animation film, Monkey King: The Hero Is back (2015), combined with a song titled “Wu Kong” by Dai Quan, is so popular that it has been played for about 2.7 million times in less than one year after it was posted in June 2015. As I examine the video in May 2016, during the three minutes playback time, one sentence keeps appearing in the barrage subtitles, “Qitian dasheng Su Wukong, shen ru xuantie, huoyan jinjing, changsheng bulao, haiyou qishi’er bian 齐天大圣孙悟空,身如玄铁,火眼金睛,长生不老,还有七十二变,” which means “Great sage Sun Wukong, Equal of Heaven, with a body like black iron, golden-gaze fiery eyes, immortal, and seventy-two transformations.” Numerous barrage subtitles containing this sentence scroll across the screen, or appear in a vibrant color at the center of the screen, or form a colorful screen of texts over the screen (Figure 1). Posting this sentence in barrage subtitles have become a ritual. This line is one of the most famous in the animation film, that a little fan of Sun Wukong, a little monk keeps repeating his own legend to the depressed Monkey King. The collective repetition of an iconic line directly refers to the high-grossing animation film, and towards the intertextual network consisting of numerous texts derivative from the ultimate source of the story, the vernacular novel Journey to the West, a book often dated back to mid-Ming Dynasty around the 16th century. In the animation film, the little monk and fan of Monkey King recites fluently this line, celebrating his personal hero in a mode that many Chinese children do. By repeating this line, the audiences are reprising the iconic scene of the film, referring to a similar childhood experience and impersonating the little monk in the film. The intertextual network that the fan video relies on goes far beyond the animation film, but to a collective childhood experience. Moreover, Monkey King is the all-time popular hero for Chinese children. Through several fandoms and fads since the late-1990s, including Stephen Chow’s The Chinese Odyssey (1995) and Jin Hezai’s Biography of Wukong, Monkey King himself through various metamorphosis, becomes a national hero that refers nostalgically to an almost nationally shared childhood as well as a national past and legacy. The target audience of the video and the community built up by the barrage subtitles are those who identify with this cultural nationalistic narrative told in the remix of the domestic animation and a song that borrows tunes from Peking Opera.

Figure 1 Screenshot on May 6, 2016 of the Monkey King remix by Miaoxingrentingge at 02:56 as appeared on Bilibili

Another example displays the ritual for commentators directly through the pictorial quality of barrage subtitles. There is a transformation process, which is ridiculously long, but is presented exactly the same way in every episode, in the anime Penguindrum 輪るピングドラム (2011). From a certain episode on, whenever this transformation process begins in the video, viewers start posting ASCII art of little rockets in the barrage subtitle in various colors. The screen will be covered by flying little rockets rapidly scrolling from the right to the left of the screen during the whole process of character transformation (Figure 2). Frequent viewers of a particular series of anime build up ritualistic conventions in barrage subtitles showing a sense of community and collectivity, or more straightforwardly, the ability to type exactly the coded language agreed by the fans of this anime and by the otaku community.

Figure 2 Screenshot made on May 6, 2016, of Ep 03 of Penguindrum at 04:47, uploaded by 96 Mao@141.2cm as appeared on Bilibili.

In both aforementioned examples, barrage subtitles have transcended the function of verbal communication, turning into a collective performance and spectacle. Daniel Johnson suggests that these comments are “counter-transparent writings,” by which he describes the heavily coded language that “disrupt the viewer’s ability to understand what is being written through their use of wordplay and movement between linguistic and pictorial registers of communication” (306). Barrage subtitles, according to him, are often written in the subcultural dialect indecipherable for outsiders. As a result, such writings play two roles simultaneously, one is linguistic communication, and the other is pictorial registration. Both functions lead to communication that is partly exclusive towards the language community. The comments in the Monkey King fan video show their direct registration towards the insiders of the fan community. Through the continuous repetition of one sentence, the barrage subtitles create a space of common knowledge and a visual spectacle.

Barrage subtitle websites including Niconico and Bilibili are a space of affect for otaku audience, who constantly experience a sense of community through pseudo-synchronicity and through a subcultural dialect consisting of counter-transparent language and memes. The videos streamed online could be understood metaphorically as a theatrical play that constantly invites, or even forces participation from audience. Audience’s performance in this play then add into the play, turning a play without the fourth wall into a carnival. Not to suggest that the community on barrage subtitle websites is a utopia outside the commercialized and globalized world, I only suggests that barrage subtitles have the potential for alternative socializing and communication. It is a new media and form; only the technophobia would read the doom for meaning from it.

Reference

“Dongman wangzhan Bilibili zhan jiang dazao er ciyuan wei zhuliu wenhua.” 动漫网站Bilibili站将打造“二次元”为主流文化. Zhongguo dongman chanye wang 中国动漫产业网. 14 Sep 2015. Web. 6 Jun 2016. <http://www.cccnews.com.cn/2015/0914/71526.shtml>.

“Guangdian zongju guanyu jiaqiang dianshi donghua pian bochu guanli de tongzhi 广电总局关于加强电视动画片播出管理的通知 (Notification from SARFT concerning Intensification of the television animation broadcasting).” Zhongguo wang中国网. 20 Feb 2008. Web. 6 Jun 2016.

96 Mao@141.2cm 96猫@141.2cm. “[Man danmu heji] Huizhuan qi’e guan [tianshi/jiying] (3)”【满弹幕合辑】回转企鹅罐【天使/极影】(3). Online video clip. Bilibili. Bilibili, 16 Jan 2012. Web. 6 Jun 2016. <http://www.bilibili.com/video/av200465/index_3.html>.

Anderson, Benedict. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism (revised edition). London: Verso, 2006. Print.

Azuma, Hiroki. Otaku: Japan’s Database Animals. trans. Jonathan E. Abel and Shion Kono. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009. Print.

Burgess, Jean and Joshua Green. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge: Polity, 2009. Print.

Coppa, Francesca. “Writing Bodies in Space: Media Fan Fiction as Theatrical Performance.” The Fan Fiction Studies Reader. Eds. Karen Hellekson and Kristina Busse. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014. 218-237. Print.

De Kosnik, Abigail. “What Is Global Theater? Or, What Does New Media Studies Have to Do with Performance Studies?” Performance and Performativity in Fandom. Eds. Lucy Bennett and Paul J. Booth. Spec. Issue of Transformative Works and Cultures 18 (2015). n. pag. Web. 20 Apr. 2016.

Fiske, John. “The Cultural Economy of Fandom.” The Adoring Audience. Ed. Lisa Lewis. London: Routledge, 1992. 30-49. Print.

Hamano Satoshi 浜野智史. “Niconico Dōga no seiseiryoku” ニコニコ動画の生成力 (The Generativity of NicoVideo). Tokushū: Generation. Eds. Azuma Hiroki and Kitada Akihiro. Nihon Hōsō Shuppan Kyōkai, 2008, 313–354. Print.

Hebdige, Dick. Subculture: The Meaning of Style. London and New York: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Ito, Mizuko. Introduction. Fandom Unbound: Otaku Culture in a Connected World. New Have: Yale University Press, 2012. xi-xxxii. Print.

Jenkins, Henry. Textual Poachers: Television Fans & Participatory Culture. New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

---. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York and London: New York University Press, 2006. Print.

Johnson, Daniel. "Polyphonic/Pseudo-synchronic: Animated Writing in the Comment Feed of Nicovideo." Japan Studies 33.3 (2013): 297-313. Web. 15 Apr. 2016.

Kimura, Tadamasa. “Keitai, Blog, and Kuuki-wo-yomu (Read the Atmosphere): Communicative Ecology in Japanese Society.” Ethnographic Praxis in Industry Conference Proceedings. V2010.1(2010): 199-215. Print.

Kinsella, Sharon. “Japanese Subculture in the 1990s: Otaku and the Amateur Manga Movement.” Journal of Japanese Studies. 24:2 (1998): 289-316. Print.

LaMarre, Thomas. “Otaku Movement.” Japan after Japan. Eds. Tomiko Yoda and Harry D. Harootunian. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006. Print.

Lancaster, Kurt. “Performing in Babylon—Performing in Everyday Life.” The Fan Fiction Studies Reader. Eds. Karen Hellekson and Kristina Busse. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2014. 198-217. Print.

Lewis, Lynn C. “The Participatory Meme Chronotope: Fixity of Space/Rapture of Time.” New Media Literacies and Participatory Popular Culture across Borders. Eds. Bronwyn T. Williams and Amy A. Zenger. New York and London: Routledge, 2012. Print.

Lin, Pin 林品 and Gao, Hanning 高寒凝. “Wangluo buluo cidian: erciyuan zhai wenhua.” 网络部落辞典:二次元·宅文化 (Internet Tribal Dictionary: Two-Dimensional and Otaku Culture). Tianya天涯. 1 (2016): 173-188. Print.

Miaoxingren tingge喵星人听歌. “Ran qilai! Tongbulü baobiao! Dang Xiyouji zhi dasheng guilai MV yudao Dai Quan laoshi yuanchuang gequ Wukong.” 燃起来!同步率爆表!当《西游记之大圣归来》MV遇到戴荃老师原创歌曲《悟空》. Online video clip. Bilibili. Bilibili, 29 Jun 2015. Web. 6 Jun 2016. <http://www.bilibili.com/video/av2498218/>.

Nozawa, Shunsuke. “The Gross Face and Virtual Fame: Semiotic Meditation in Japanese Virtual Communication.” First Monday. 17.3-5 (2012): n. pag. Web. 15 Aug. 2015.

Strangelove, Michael. Watching YouTube: Extraordinary Videos by Ordinary People. Toronto, Buffalo, London: University of Toronto Press, 2010. Print.

Wochong卧虫. “Danmu, he’ermeng, ciyuan qiang he zuowei yijia gongsi de bilibili” 弹幕、荷尔蒙、次元墙和作为一家公司的哔哩哔哩. Pingwan 品玩. 8 Dec 2015. Web. 6 Jun 2016. <http://www.pingwest.com/bilibili-family/>.

Xiqing Zheng is an assistant professor at the Literature Institute, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Beijing, China. She received her doctorate in comparative literature from the University of Washington in 2016. Her research interest includes fan culture, new media, Chinese cinema, translation, etc. Her current project is working on revising her dissertation, which is based on online fan subculture, mainly in China, but also in Japan and in the English speaking countries. She is the Chinese translator of Henry Jenkins' Textual Poachers. She is also a consultant of the Internet Literature Studies Forum of Department of Chinese Language and Literature, Peking University, and participated in writing a book of keywords on Chinese subculture, which will be published this year by Joint Publishing. An avid fan for more than ten years, she mainly serves as a fan translator online and occasionally creates fan fic and fan art.