My fanboyish ejaculations on Antonioni's films a couple of posts earlier drew startled responses from a couple of friends (Bhaya and Anurag, this is for you!). They felt that it deviated from the norms of pseudo-intellectual pretentions that this blog generally displays. And after all, being a pseudo-intellectual, how can you just "like" something without giving a proper theoretical justification or dropping a few names, preferably from the western tradition? Also, my saying that I like depressed and beautiful women was found to be shockingly childish. So this post is an exercise in damage control, an attempt to restore the reputation of being a pseudo-intellectual. In what follows I explain why I like Antonioni (specially those three films, L'Avventura, La Notte and L'Eclisse) in a very pseudo-intellectualish way of course:

My fanboyish ejaculations on Antonioni's films a couple of posts earlier drew startled responses from a couple of friends (Bhaya and Anurag, this is for you!). They felt that it deviated from the norms of pseudo-intellectual pretentions that this blog generally displays. And after all, being a pseudo-intellectual, how can you just "like" something without giving a proper theoretical justification or dropping a few names, preferably from the western tradition? Also, my saying that I like depressed and beautiful women was found to be shockingly childish. So this post is an exercise in damage control, an attempt to restore the reputation of being a pseudo-intellectual. In what follows I explain why I like Antonioni (specially those three films, L'Avventura, La Notte and L'Eclisse) in a very pseudo-intellectualish way of course:

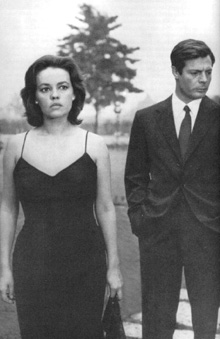

First, depressed beautiful women. Let me put it this way. I love the portrayal of a profound sexual melancholy in Antonioni's films, in his female characters specially. Sexual melancholy, as in, when you are feeling completely isolated, disconnected and alienated from your surroundings and yet deeply long for a serious erotic union with the Other. Or, in less pretentious terms, you are feeling sad, alone and horny all at the same time. Antonioni connects sexual desire with a general anxiety and uncertainty that the characters feel about everything and which gradually eats away at their souls. No wonder that Monica Vitti after being depressed in all these three films finally reaches mental asylum in Red Desert, which is a continuation of the trilogy.

Second, getting away from the classical concerns of character or narrative. Antonioni took narrative cinema away from straight storytelling, towards a realm where he could explore ideas in a more direct manner.  People looking for narrative closure and clean-cut explanations for character behavior will be disappointed with his films. What is important there, is the "mood", which Antonioni creates and sustains by employing very stylish camera work and scene compositions. And through this he explores the ideas in a purely visual manner. But what exactly are those ideas? Feelings of radical alienation and disconnection from the surroundings and from other human beings, that have become an inevitable part of modern urban life, find a potent expression in his films and specially in the face of Monica Vitti and Jeanne Moreau. His films are a critique of the idea of modernity and document the costs of material prosperity in terms of wasted human lives and potential for genuine happiness and fulfillment. The most common symbol he chooses to show this is that of modern architecture. All those empty buildings, which in their weird geometric shapes, just seem to be completely devoid of any human element whatsoever. As if the world itself is trying to reject humanity. The same is for the emptied streets on which Monica Vitti spends most of the time just walking aimlessly. It's the streets and roads which have deserted human beings, not the other way round.

People looking for narrative closure and clean-cut explanations for character behavior will be disappointed with his films. What is important there, is the "mood", which Antonioni creates and sustains by employing very stylish camera work and scene compositions. And through this he explores the ideas in a purely visual manner. But what exactly are those ideas? Feelings of radical alienation and disconnection from the surroundings and from other human beings, that have become an inevitable part of modern urban life, find a potent expression in his films and specially in the face of Monica Vitti and Jeanne Moreau. His films are a critique of the idea of modernity and document the costs of material prosperity in terms of wasted human lives and potential for genuine happiness and fulfillment. The most common symbol he chooses to show this is that of modern architecture. All those empty buildings, which in their weird geometric shapes, just seem to be completely devoid of any human element whatsoever. As if the world itself is trying to reject humanity. The same is for the emptied streets on which Monica Vitti spends most of the time just walking aimlessly. It's the streets and roads which have deserted human beings, not the other way round.

Third, his concern with the mise-en-scene and scene composition. Antonioni was perhaps the most stylish filmmaker of his generation. What is most remarkable is how he composes his scenes specially how he chooses what to put in background and what in foreground. Normally, in a scene the protagonist will occupy the centre of the frame and the entire focus will be on him with the background there only to supply the context, or as in Hollywood films, to make the scene look "beautiful" (in the most cliched way of course). In Antonioni's films the background is a character in itself, sometimes even more important than the protagonists in front of them. For example, in that brilliant island sequence of L'Avventura, it is that landscape which occupies most of the frame, with the characters there only in corners, or else, shot in such long shots as to make their personality relatively unimportant as compared to those landscapes. It creates a weird disorienting effect in the viewer. Also remarkable is the scene where Claudia and Sandro make love in an open field. It is shot in such an unconventional style, that just by watching the sex scene, you get the idea that it is an empty sexual connection, one that is not going to last.

Fourth, cinema of absence. What troubles many people when watching these films is why do the characters just walk and walk on those empty streets? Why are the buildings always vacant? And in general, why is there so much of open space everywhere? I think it is a very radical idea, the idea that you can comment on something by NOT showing something where it was expected. It is in this context that the brilliant ending of L'Eclisse makes sense.  The two lovers in the end promise to meet once again to continue their affair but looking at their faces and the way they utter those words, it becomes clear that it is an empty promise after all. What follows is a long (seven minutes) sequence of silent shots of the place and its neighbourhood where they were supposed to meet. It is by the emptiness in those spaces that we find out that the spark of love has indeed died and that it is truly THE END in every sense of the term. The final scene is that of a street lamp which resembles an eclipse, perhaps signifying an apocalypse or the end of the world itself.

The two lovers in the end promise to meet once again to continue their affair but looking at their faces and the way they utter those words, it becomes clear that it is an empty promise after all. What follows is a long (seven minutes) sequence of silent shots of the place and its neighbourhood where they were supposed to meet. It is by the emptiness in those spaces that we find out that the spark of love has indeed died and that it is truly THE END in every sense of the term. The final scene is that of a street lamp which resembles an eclipse, perhaps signifying an apocalypse or the end of the world itself.

Fifth, cinema of silence. There is a general tendency in people that when there is no sound coming from the screen they shut down their sensory perceptions. That's the reason why background score is so ubiquitous in Hollywood movies, or for that matter any cinema which relies solely on "action". In contrast, Antonioni's cinema is a cinema of thoughts, moods and ideas. What makes these films even more masterful is that Antonioni relies solely on visual style. Dialogues can never get you inside the head of the character, specially when the characters in question are feeling alienated, that's why there are so many silent scenes and even when someone speaks something it does nothing to propel the plot forward. So on the surface you get the feeling that "nothing is happening" but it is inside the head of those characters that things are happening which is like it is in the real world too.

Sixth, the impossibility of love in the modern world. These three films are some of the most eloquent essays on the phenomenon of the breakdown in human relationships, specially in the advanced and modern societies. What makes these films so disquieting and despairing is that Antonioni doesn't treat it as a problem which has anything to do with the individuals in question but rather treats it just as a symptom, a symbol signifying a far deeper malaise in the society. It is in this context that the final reconciliatory scene (or is it?) in L'Avventura makes sense. In modern societies we have done away with the moorings of tradition, family, religion or community but haven't replaced them with anything substantial. Eros in itself isn't powerful enough a force to keep people together, that's what Antonioni suggests. In a remarkable scene in L'Eclisse towards the end, sensing that her relationship with her stockbroker boyfriend is going to end Vittoria says, "I wished I didn't love you or I loved you much more". It is this uncertainty towards everything which has crept in our consciousness, because we have forsaken the certainties, false of course, of religion or tradition, that is creating havoc in our lives, ultimately leading to unhappiness, ennui and anxiety.

In modern societies we have done away with the moorings of tradition, family, religion or community but haven't replaced them with anything substantial. Eros in itself isn't powerful enough a force to keep people together, that's what Antonioni suggests. In a remarkable scene in L'Eclisse towards the end, sensing that her relationship with her stockbroker boyfriend is going to end Vittoria says, "I wished I didn't love you or I loved you much more". It is this uncertainty towards everything which has crept in our consciousness, because we have forsaken the certainties, false of course, of religion or tradition, that is creating havoc in our lives, ultimately leading to unhappiness, ennui and anxiety.

Finally Antonioni's influence. Antonioni was easily the most stylish and radically innovative filmmakers of his generation and it his style and thematic questions that concern most of the great filmmakers currently working, specially those exploring the phenomenon of alienation and urban isolation and dislocation like Michael Haneke, Wong Kar-wai, Tsai Ming-liang and others. They all trace their pedigree to Antonioni. He has been responsible for freeing narrative cinema from the pre-modern shackles of conventional storytelling and brought cinema back to the level of literature (well, almost) of its time.

Anyway if you are in New York, don't miss the Antonioni retrospective which is on at the BAM cinematheque all this week. Details here. I can only imagine what kind of experience it would be to watch L'avventura on the big screen for the first time. I had earlier linked to the articles about the retrospective in NYT and Village Voice.

I had earlier written a post on L'Eclisse. You can find it here.