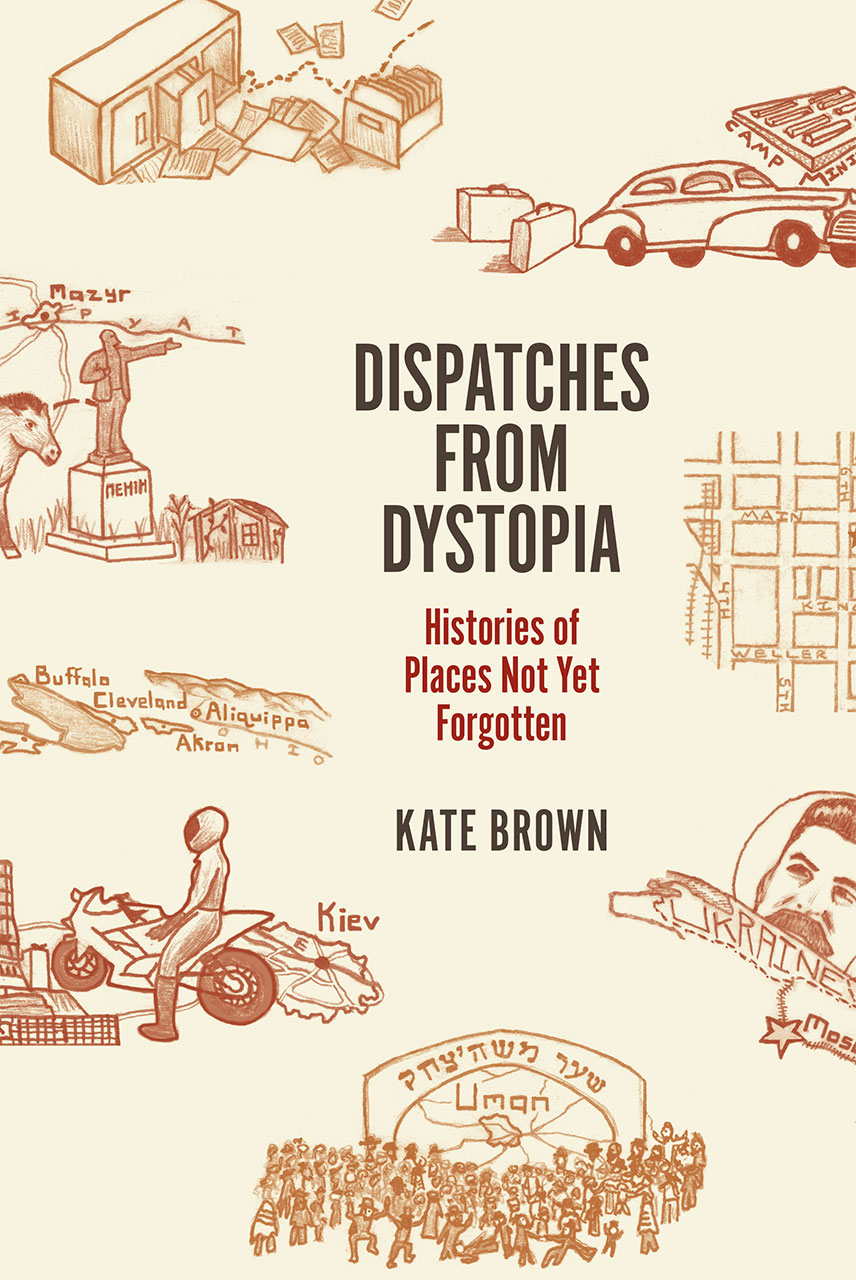

This book was a little different than what I expected, though I am not sure what exactly I expected. It is really beautifully and empathetically written, though Brown herself has more of a role in the essays than I expected her to. She acknowledges this at the very beginning, saying that it is difficult for her to be a third party observer when she is in the midst of the story herself. So instead of talking about the places and the people themselves, she talks about her interactions with the people and places she visits. In this way, Kate Brown reminds me of Rebecca Solnit.

I really enjoyed this book, mostly because it gives a new perspective on many different places. Very real to me was the chapter on Seattle's Panama Hotel, where many Japanese-Americans left their belongings before they were sent to internment camps during World War II. Brown talks about how some words were used over others to make the whole thing seem more palatable, how people were taken away quietly and away from others so that no one had to see what they had brought to bear:

White Seattleites in February 1942 voted overwhelmingly for the Japanese Americans' removal. Imagine their reaction if Japanese American deportees had left their possessions in plain sight: rain-soaked laundry dangling from clotheslines, produce rotting on fruit stands, goods in shop windows fading in the sun. The unrepressed possessions of suddenly absent fellow citizens would have told a story starkly divergent from newspaper accounts of "evacuation," safety, national security, and inevitable fealty to race. The basement full of belongings underscores the myth of what was euphemistically called "evacuation," a term implying benevolence, a federal government seeking to remove Japanese Americans for their own safety. Like the deportations - indeed, like the deportees - the stockpile was meant to be forgotten. To me, the Panama's storage room of locked-away possessions served as an icon for the quiet banishment of Japanese Americans from American society.Much of Brown's book revolves around multiple ways of looking at either the same scene or the same situation and acknowledging the different biases or assumptions that get people to those viewpoints. For example, she describes how American scientists looked at the impact of radiation on people by first studying the environment and what the minimum exposure level of a person was to an environment; Soviet scientists looked at people, saw the symptoms, and made diagnoses based on the person, not the environment. The approaches reached different conclusions and led to different pros and cons. The American method has now encroached on how we view almost all environmental disasters and impacts - upon individuals, not upon a whole system.

One of my favorite things about this book was the way Brown insists that we change our perspective on people who live their lives differently than we do. She visits Chernobyl expecting to see so many horrors, but she sees that some people do still live there. She visits another town, Pripyat, that has since been abandoned because of a nuclear explosion but that was really quite a beautiful, idyllic place to live when things were going well. Meaning, just because people lived in the Soviet Union, that doesn't mean they were all unhappy and miserable all the time. They had good lives, too.

Brown's last chapter takes her to Elgin, Illinois, a town not so far from where I grew up. She tells a story that is now familiar to many of us that grew up in America's heartland, the steel belt turned rust belt, the towns that many feel have been left behind as jobs and people and money go to the cities. But Brown also tells the flip side of the story, of how those towns often made decisions that hurt themselves in the long run, choosing short-term profits and cost-cutting over longer-term investment. When workers at the main employer in Elgin went on strike to fight for better wages, the company response was fierce and immediate. "For the following century, the company suffered no more strikes, and Elgin leaders enticed other manufacturers to town with tax breaks, land grants, and arguments that Elgin was 'a poor field for the agitator.'"

And so, even though unemployment was low, people continued to work well past the age of retirement, and 40% of married women continued to work after marrying and having children to support their families. And then the factory left, anyway, to find even cheaper labor. Brown talks about how, for such a prosperous country, America has many towns that look abandoned and left behind, almost ghost-like. "These are the muted smells and sounds of amputated careers and arrested bank accounts. Looking at the chain of churches and shops displacing one another in quick succession, feeling something between depression and despair, I think about E.P. Thompson's question - who will rescue these places from the enormous condescension of posterity?"

In some ways, Dispatches from Dystopia has the same central premise as Strangers in their Own Land - we need to give people who feel forgotten and left behind a platform from which to speak and feel valued and empowered, rather than just telling their stories from our perspectives. But perhaps because Kate Brown made the decision to go to multiple places, to draw parallels between towns in America and towns in the Communist bloc, the American approach to science and free will vs the Soviet approach, it felt much wider-reaching. So much of what we believe is based on justifying acts, making ourselves feel better, like using the word "evacuation" instead of "imprisonment." Talking about "diversity" instead of "equality." And it's only when we really push ourselves to make those connections, draw the parallels, that we can fully acknowledge what we've done and what we can do going forward.

Are you interested in learning more about this subject?:

I put up loads of links at the end of my reviews on Strangers in their Own Land and The Unwinding.

If you would like to watch a documentary about the women who still live in the Chernobyl zone, check out The Babushkas of Chernobyl.

While there, you can listen to Holly Morris' TED Talk about the women and what happy, peaceful lives they are living, contrary to what all of us would generally believe.

Holly Morris' story about the Babushkas is also included in this episode of the TED Radio Hour, Toxic.