|

|

By Jonathan Amos

Science reporter, BBC News

|

|

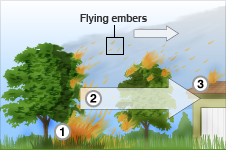

HOW BUSHFIRES SPREAD

1 Fires start in hot dry windy weather

2 Embers blown ahead of fire front

3 Spot fires start where embers land

|

Bushfires are an expected hazard for the people who live in the Australian state of Victoria, but the scale of the weekend's disaster has left everyone shocked.

Scientists understand the processes which trigger fires all too well and recent conditions have been shown to be frighteningly perfect.

It has been extremely warm with temperatures over 40C. Strong winds have also been blowing from the interior of the continent.

"In south-east Australia, bad fire days are associated with the presence of a 'blocking' high pressure system in the Tasman Sea. This brings hot, dry strong wind from the centre of the continent to the south-east," said Andrew Sullivan, a fire researcher with Australia's lead scientific agency, CSIRO.

"The high temperatures and dry air experienced throughout Victoria on Saturday resulted in very low fuel moisture content. Combined with the extended rainfall deficit for much of the state, this resulted in tinder-dry fuel that was very easily ignited and very difficult to extinguish."

'Fire weather'

The region has been in the grip of the "Big Dry" - the worst drought in a century.

Last week, a group of Australian researchers produced a report in which they said a dominant factor behind this extended dry period was a phenomenon known as the Indian Ocean Dipole.

This is said to relate to a flip-flop pattern of ocean temperatures found to the west and north of the Australian continent.

In the "negative" phase, cool waters rule off the west of the continent and warm waters dominate in the Timor Sea to the north. This produces winds that pick up moisture from the ocean and sweep it down towards southern Australia to deliver cool, wet conditions.

In the "positive" phase, the pattern of ocean temperatures is reversed. The winds are weaker, they cannot pick up so much moisture, and south-eastern Australia experiences drier conditions.

|

The consequences of attempting to work against Nature, by trying to prevent any fires at all, can be catastrophic

The consequences of attempting to work against Nature, by trying to prevent any fires at all, can be catastrophic

|

The problem, the team from the University of New South Wales said, was that the dipole seemed to be stuck in its "positive" phase.

The researchers studied long data sets to show correlations not just between current events but also the major droughts at the beginning of the 20th Century and during the WWII.

The dipole idea is not universally accepted among climatologists. Many see the El Nino phenomenon centred on the Pacific as being the most important signal.

One of the inevitable questions is how climate change might affect such natural cycles. Scientists will investigate the links further and use powerful computer models to try to tease out the probabilities.

Current climate projections point to an increase in fire-weather risk from warmer and drier conditions.

Two simulations used by Australia's lead scientific agency, CSIRO, and the Australian Bureau of Meteorology point to the number of days with very high and extreme fire danger ratings increasing by some 4-25% by 2020, and 15-70% by 2050.

The agencies' Climate Change in Australia report cites the example of Canberra which may be looking at an annual average of 26-29 very high or extreme fire danger days by 2020 and 28-38 days by 2050.

Back-burning

What is clear though is that fire is part of a natural process in some ecosystems. Many plant species have evolved as part of a fire system.

Burning causes organic matter to decompose rapidly into mineral components which cause plants to grow fast, and it recycles essential nutrients, especially nitrogen.

Left to its own devices, Nature will initiate - usually through lightning strikes - regular "cool fires" which burn out grasses and shrubs but leave trees charred though not destroyed.

Humans, if they want to live in these types of locations, have to learn to manage their surroundings.

Principally, this means not letting the undergrowth build up, to provide the "ladder" that would otherwise allow fires to consume trees, also. In such circumstances, cool fires rapidly become very hot - and very destructive - ones.

It is why authorities in fire-prone districts across the world - not just in Australia - will practise back-burning, or the controlled ignition of undergrowth.

This type of management is not always popular. Residents dislike being smoked out of their homes every time it is done and some people will resent having the pleasant view from the porch turned to a blackened mess.

There is a natural fear also that such burning might get out of hand and result in the kind of damage it is trying to prevent.

But the consequences of attempting to work against Nature, by trying to prevent any fires at all, can be catastrophic.

David Packham, who has studied bushfires and meteorology for many decades, said at the weekend that Australia had ignored the warnings on this for far too long; and that Victoria was paying the price for allowing fuel loads to build up to unprecedented levels.

"The mismanagement of the south-eastern forests of Australia over the last 30 or 40 years by excluding prescribed burning and fuel management has led to the highest fuel concentrations we have ever had in human occupation," said the researcher from the Climatology Group at the School of Geography & Environmental Science, at Monash University.

"The state has never been as dangerous as what it is now and this has been quite obvious for some time."

|

~RS~q~RS~~RS~z~RS~12~RS~)

Bookmark with:

What are these?