at the other side...

bad, bad, bad... part 2 (7/1)

Answering question 2: What is the poetry I gravitate toward?

*

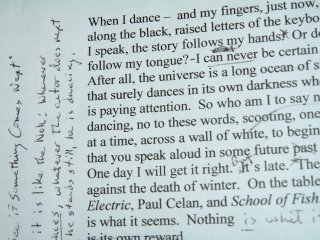

#2 – The poetry I gravitate toward is of no set school, tradition, or lack of tradition, no set form or content, no set language or culture. I gravitate toward poems that make me pause, make we read them again – poems that make me move mentally, emotionally, spiritually… whatever… into a larger place. As to form or style, I’m eclectic in my reading, or tend to be.

Here’s a poem - certainly for changing eye and hand - by Ted Kooser that is as close to perfection as I can imagine. The poem takes me in, and there’s no way to return. I can never get to the end of this piece, and that's wonderful. That’s what I want from poetry.

After Years

Today, from a distance, I saw you

walking away, and without a sound

the glittering face of a glacier

slid into the sea. An ancient oak

fell in the Cumberlands, holding only

a handful of leaves, and an old woman

scattering corn to her chickens looked up

for an instant. At the other side

of the galaxy, a star thirty-five times

the size of our own sun exploded

and vanished, leaving a small green spot

on the astronomer’s retina

as he stood on the great open dome

of my heart with no one to tell.

- from Delights & Shadows

I’m drawn to the metaphysical, certainly, to lines that ache with image and music, that tend to move away from causes, from the political - mainly because the cause poem is, by and large, a poem of the moment and not of the universal. Often, the poetics of the moment is too controlled by the cause or event. Too restrained by the cause. There are exceptions, of course. I have to note that Lorca, who is listed below, is a political poet. But I think his politics are internalized. Snyder, another example, is a writer who combines environment and politics to such an extent that it's impossible to separate the two. That is a great quality in his work.

In the truest - or maybe deepest is the best term - sense, every poet is political... if the voice is honest, is true. I’m thinking know of Adrienne Rich who stated that if the poet doesn’t come to terms with her or his deepest self, the poetry may be good, may possess a form that is pleasing, even be popular, but the poetry will be superficial. “Diving into the Wreck” – a poem about the creative experience, about the nature of life – is most certainly one of the three or four most important poems in my life. But, I should add that The Dream of a Common Language is my choice as her finest collection. I think that work is the closest the reader gets to Adrienne, the person. I do consider Rich to be a political poet.

William Stafford is a poet – wielding major influence on my own poetic self – whose poetry is absolutely political, yet the political view is subtext, is the necessary blood of his writing. Every Stafford poem is fused with the force of his stand against war. That is vital to understanding the world of his poetry, as well as the nature of his craft.

*

A small list of poets – and in no particular order – from a glance at the poetry books on one shelf beside my computer: Jorge Luis Borges, Wislawa Szymborska, Eileen Myles, José Garcia Villa, Paul Celan, Yusef Komunyakaa, Mary Ruefle, Jelaluddin Rumi, Denise Duhamel, Tory Dent, Bob Hicok, Gerard Manley Hopkins, Joy Harjo, Rusty Morrison, Carl Phillips, Ryōkan, Arthur Rimbaud, Anne Carson, Robert Herrick, Lucille Clifton, Frank Stanford, H.D., and Czeslaw Milosz.