I do not recommend this book, but I gave it a gentle review in the hope that the kind of people who read this kind of book might be interested in reading further and deeper.

Helpful votes are always appreciated - I'm now at 2,285 and aiming for under 2,000.

|

|

| ||||||||||||

Amazon Verified

Purchase(What's this?)

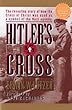

This

review is from: Hitler's

Cross: The Revealing Story of How the Cross of Christ was Used as a symbol of

the Nazi Agenda (Kindle Edition)

I began a project of reading

scholarly history books on the Nazi relationship with Christianity because of

the atheist claims that "Hitler was a Catholic" or "Hitler was a Christian."

After reading Richard Stegman-Gall's The Holy

Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919-1945 and Susan Heschel's The Aryan

Jesus: Christian Theologians and the Bible in Nazi Germany and Kevin

Spicer's Resisting

the Third Reich: The Catholic Clergy in Hitler's Berlin and Hubert Wolf's Pope and

Devil: The Vatican's Archives and the Third Reich and Derek Hastings' Catholicism

and the Roots of Nazism: Religious Identity and National Socialism, my

conclusion is that the truth is far more complicated and far more interesting

than a simple yes or no answer can provide. The warm relationship between the

Nazis and the Christian churches at an early stage had a lot to do with the

particular history of Germany, which included a pent up sense of nationalism,

but also a healthy dose of what we would call "liberal Christianity," which was

willing to "re-imagine" Christ and the biblical canon in order to make

Christianity "relevant" to "modern times."As a result of this background reading, I came Erwin Lutzer's Hitlers Cross with a great deal of interest. I had thought that the book might be a scholarly work that reviewed the history of the Nazi's subversion of Christian symbols for their own purposes. What I discovered was a book that really is an extended sermon, written from very few sources, by the Senior Pastor of the Moody Bible Church, as if he was giving a sermon to his congregation. For example, there are a number of occasions where Lutzer drops into rhetorical tropes that obviously come from Mr. Lutzer's clearly well-practiced skills a public speaker. This book is really Lutzer's attempt to come to grips with the problem that so many Germans, German Christians and German Christian pastors in the Nazi era either were willing accomplices of the Nazis or, at best, were compliant non-objectors to the evils of Nazism. Lutzer looks at various explanations, including occultism, Hinduism, German history, and the influence of Luther. Lutzer also stirs in what he finds to be parallels to trends in the America that he was writing about in the mid-1990s, trends, frankly, that have accelerated. It is Lutzer's conclusion that Hitler was an avowed Satanist who swore allegiance to Satan before the Spear of Destiny in Hofburg museum. (p. 64 - 66.) As a result, Lutzer infers that Hitler was imbued with occult powers to mesmerize his audiences and subordinate them to his will. I've never heard of the "Spear of Destiny" story in any of the books I've read. Lutzer's source for this story is Trevor Ravenscroft The Spear of Destiny: The Occult Power Behind the Spear which pierced the side of Christ , which a little internet research indicates is not a trustworthy source. Lutzer, for example, quotes verbatim a lengthy verbatim quote from Walter Stein as quoted by Ravenscroft, but Ravenscroft never met Stein, and much of Ravenscroft book is written in an obviously novelistic style with gross misstatements of fact. (Google "Bad Archeology Spear Lance Destiny Hitler".) Interestingly, Ravenscroft's book may have been an inspiration for "Raiders of the Lost Ark," one of whose major characters was "Marion Ravenwood." The occult connection with Nazism is problematic. Some Nazis - for example, Heinrich Himmler - were drawn to occultism. (See Peter Longerich's recent, encyclopedic Heinrich Himmler.) Others were not. Goering, for example, seems to have conceived of himself as a pious Lutheran throughout his career and viewed the pagan excesses of Himmler as "nutty." Even Hitler put the brakes on Himmler when Himmler went "over the top." (That's not to say that any of these people were Christian or committed to anything other than the complete revision of Christianity along Nazi lines.) Lutzer likewise seems to blame Hinduism for providing something to Nazism (p. 91), albeit he affirms that he doesn't intend to blame Hinduism (p. 96.) It is true that study of Hinduism was influential in Germany in the 19th Century and that Himmler, at least, read some scholarly works on Hinduism in his youth, but in my reading of Longerich's massively encyclopedic tome on Himmler, Hinduism is not mentioned as a substantial influence on him. Notwithstanding Lutzer's assertion, Himmler's statement about "decency" has more to do with being civil and courteous than it has to re-incarnation. Lutzer also considers German history, including the influence of Luther. Although a lot of this analysis is based on a popular understanding of history as viewed through modern American evangelical eyes - apparently there was a healthy undercurrent of real Christians throughout the Middle Ages who refused to baptize children - to his credit Lutzer is willing to lay some of the blame for German anti-semitism on the unfortunate anti-semitic writings of the later Luther, although Lutzer walks back some of that blame by contextualizing it, which may be a fair thing to do, since, in the words of historian Robert Louis Wilken, "every act of historical understanding is an act of empathy." (See John Chrysostom and the Jews: Rhetoric and Reality in the Late 4th Century.) Of course, running through Lutzer's book is the sheer existential mystery of evil. Our ability to understand may forever elude us because there are, quite properly, limits to our ability to empathize. And yet empathize we ought to because we share with those Christians in Nazi Germany the same human propensity to "screw up" as they had. (For an interesting discussion on this propensity, see Unapologetic: Why, despite everything, Christianity can still make surprising emotional sense.) Lutzer's sermonizing style may therefore not be inappropriate. Nor may it be inappropriate to discuss the Nazi era in terms of biblical truths and prophecies. We want to understand it so that we can explain it, but we also want to have some distance from it so we don't have to own it. However, Lutzer's theology doesn't make Lutzer's book history. He makes some real errors in history, both large and small, and often-times the small errors are the most impeaching. Thus, Lutzer incorrectly asserts that Houston Chamberlain was the nephew of Sir Neville Chamberlain (p. 89.). This is not true, and I was surprised that I had never heard such a thing before. I filed this away as possibly being true, until I did sufficient research to rebut it. (Frankly, I hate being misinformed on trivia like that because I hate looking like an idiot when I repeat it.) Likewise, there was no Catholic bishop in Berlin who was arrested and died in a concentration camp for "leading his people in prayer for the Jews." (p. 146.) German Catholic bishops were shot at and threatened with arrest and would have been summarily executed after the war, and many Catholic priests went to concentration camps, but the Catholic bishops of Berlin, although heroic figures, were not arrested. Lutzer is probably thinking of the Berlin Catholic priest Bernhard Lichtenberg, who did speak out for the oppressed Jews, and who was arrested and died in a concentration camp. Lichtenberg's heroic story deserves to be more widely known. Lichtenberg's story is told in Spicer's Resisting the Third Reich: The Catholic Clergy in Hitler's Berlin. The true story is well worth reading. Another throwaway line is also problematic. Despite what Lutzer says, Poland did not receive territory that Bismarck had "conquered." (p. 30.) After World War I, Poland was reconstituted from the territory that had been "partitioned" by Prussia, Austria and Russia. Since those "partitions" had occurred in the 18th Century, and Bismarck unified Germany in the 19th Century, the Polish territory had long been "conquered" but not by Bismarck. Lutzer also does not appear to understand that the event that sparked the decision of Martin Niemoller and otehrs to form the Confessing Church was the fact that the majority of Protestant churches under the control of the German Christians had accepted the idea of removing the Old Testament from the Christian canon. This would have been a fascinating area for Lutzer to explore since it ties directly into two themes that he is very interested in, namely (a) the erosion of Christian core theology by liberal philosophy and (b) the mystery of how any bible-loving Christian could agree to such a disfigurement of God's word. If I was to rate this book as a work of history, I would give it one or two stars. I choose, however, to view this book as an effort to get evangelicals thinking about history and, in particular, the history of Christianity under the Nazis. As such, I choose to view this as introductory material that might whet the interest of those who don't know much about that history. I would recommend to any such readers, not to put too heavy a reliance on the data that you read in this book. Move on to more weighty books, like the ones, that I mentioned throughout this review, and think about what the history of that era says about our own era. I believe that such an exercise will pay dividends. | ||||||||||||||